If you could learn how to remember things quickly this year, would you?

How about if you could increase your reading speed – which books would be at the top of your list?

And how would improving your memory impact on your life?

These are just some of the questions I discuss with Jonathan Levi from Superlearner Academy, an accelerated learning programme that has changed thousands of lives.

Here's a summary of our conversation on super learning techniques:

- How Jonathan struggled at school & was always falling behind

- Are we aware of the learning challenges we face?

- Skills Jonathan has learned with accelerated learning techniques: Acroyoga, Public Speaking, Olympic Weightlifting, Aerial Photography, Advertising, Hebrew, Russian, and much more!

- Using mnemonic techniques & speedreading to learn a new skill

- How to retain information you read in a book

- Structured repetition of ideas

- Accelerated learning for foreign languages

I hope you enjoy the conversation!

Pro Tip

If you want to learn a new language, while study skills are important, using the right method is also key.

My courses teach you through StoryLearning®, a fun and effective method that gets you fluent thanks to stories, not rules. Find out more and claim your free 7-day trial of the course of your choice.

Struggling to Learn at School & Falling Behind

Olly: Jonathan, welcome to the show, I'm super excited to have you here. I've been wanting to pin you down so we could have a proper chat for quite some time now. Why don't you just take a second and tell people who is Jonathan Levy.

Jonathan Levy: First off, thanks for having me, Olly, it's always a pleasure to kind of mind meld and chat with you, so I'm really looking forward to the call. Who is Jonathan Levy? I ask myself that every day, because it seems to be a dynamic answer. Essentially, I'm a lifelong entrepreneur, a serial entrepreneur. Currently, my current life's work is teaching people accelerated learning.

Jonathan's Story

I struggled as a student, I was always kind of a problem child. I was sort of, kind of diagnosed with ADD. My parents didn't want to actually send me in, but basically diagnosed with ADD by a special education teacher when I was eight years old. That was kind of the point when I realized that I was a little bit different and other kids seem to get this stuff and I don't.

That kind of culminated or led to me being pretty heavily medicated for most of my adolescent life, bouts with depression, anxiety, low self esteem, just because I wasn't learning. It wasn't just classroom learning, it was pretty depressing that other kids were getting good grades and I wasn't, but it was also learning around different social skills and learning around sports. I never seemed to be able to learn as quickly as other people, and I thought that was odd, because I knew I was a smart kid.

People told me I was smart, but I didn't seem to be successful academically. Medication was great, and if anyone out there struggles with ADD the way that I did, medication in many ways saved my life, at least academically and professionally. I still would forget everything as soon as I left the exam room, and that all changed for me in 2011.

I had kind of packed up, gone to this venture capital firm, and I was doing an internship before starting my Master's degree. I don't know about you, but I suffered through my undergraduate degree. I went in as Environmental Economics, that was too hard, I was trying to also run a business on the side. That was too time consuming, too much reading, had to dumb it down.

Then I went to Anthropology, that was too hard. So, I ended up changing my major three times, because I couldn't get through the reading. I ended up on Sociology, which was kind of light reading and more writing than reading, I was always an okay writer. I knew this time I wasn't going to be able to do that, I was going for a Master's in a specific subject. I wasn't going to be able to cop out in the middle and change my major if it was too hard. It was a condensed program, so eight months to do two years of material.

As soon as I was admitted, they gave me 1107 pages of reading. I was like; what the hell am I going to do?

I got really lucky, because at that time I met someone who was a speed reader and a memory expert. It turns out he and his wife had developed these techniques for teaching children with learning disabilities, and it's a lot of the stuff that probably your audience knows. It's the basic speed reading stuff that you've probably heard a million times, or maybe haven't heard at all, and mnemonic techniques.

I've always been a hacker, I've always been really interested – I've got photos from when I was 18 years old of me hooking myself up to metabolic machines and trying to find out what my VO2 max is. I've always been interested in that, and I tried speed reading a few different times and it never worked, I never absorbed anything, but opening up this whole world of mnemonic techniques was like magic to me. Suddenly I could remember things, I could read things. I ended up going on to do this MBA and be able to just power through reading.

Essentially to make a long story somewhat shorter, I found myself making a career out of reteaching these skills, which I had been taught in Hebrew. Translating them to English and finding a way that everyone could learn them, not just people who were able to afford expensive private tutoring.

Are We Aware of the Learning Challenges We Face?

Olly: There's so many questions I want to ask you just stemming from that. Let me ask you this; as a kid were you aware of the challenges that you were facing? Sometimes when you're young, the problems that you face you don't necessarily understand what they are.

So, were you aware at that time I've got a learning problem, or I've got ADD? Were you aware of that, of what you were facing?

Jonathan: Yes. I kind of knew in first grade, because I started getting report cards that my parents had to have serious conversations with. I recently went back, because you know we have this tendency, especially in the industry you and I are, to look back at our biography and be like it all makes sense, but I went back and said did it all make sense?

Identifying the Problem

Along about the time I did my TED talk, I really asked myself the question and I pulled it out and first grade it was Jonathan needs to pay more attention, Jonathan needs to understand that being the class clown is not a way to get ahead, Jonathan needs to sit still, Jonathan is falling behind the class, and they just got worse and worse.

Olly: So you knew it was a problem.

Jonathan: Oh, I knew, and also I had this tendency where I'd have to go in and have – I remember the first thing that I fell behind was reading a clock. So, in first grade you learn how to read a non-digital clock, and I remember I just couldn't get this. I remember it was so bizarre, it says 10, how is that 50 minutes?

I didn't get it, and I had this kind of tendency where I'd have to go in, someone would have to explain something to me, the next thing that was really hard for me was multiplication tables, and then I had in this moment – I don't know if you've ever had this, I don't know if normal people have this – when someone would explain it to me and it would click, I would almost start like laughing and crying, because it would be like oh, and my eyes would well up.

It was like oh, my God, it took me so long to get to this point of understanding, and just overwhelmed with emotion of why couldn't I have gotten this the first time, why did I have to ask all these questions and figure it out this way.

What Skills Can You Learn With Accelerated Learning Techniques?

Olly: I'm trying to relate that to my story. I was pretty good at school, I didn't have any particular issues– my grades were always good and I was always conscious that I was capable of doing this stuff, but I just was always resisting putting the work in that I needed to. If I knew I had an essay to hand in, I wouldn't start two or three weeks before like I should, I'd wait until the last evening.

I was always kind of like questioning myself, because I knew I was capable of it, but I just couldn't bring myself to do it. I see a lot of parallels between the Olly who didn't do as well as he could have done in his history essays and the Olly who, these days, could be so much better at language learning if he could just be strict enough with himself to say, “At 6:30 a.m., you sit down, you study for an hour. It's not hard, that's what you do”.

So, I see a lot of parallels with that. In many ways, I guess I haven't changed, but you have. You've kind of had this realization that many people never get to in their life, and you've learned these techniques, which you could easily not have done.

How Jonathan Put His Techniques into Action

Everything could be very different. In a nutshell, we'll get into these specific things in a minute, but could you give us some like visceral examples of things you've been able to do in your life as a direct result of the accelerated learning techniques that you mentioned?

Jonathan: Sure. So, I go through ebbs and flows, and by the way, I also want to comment that I have that discipline problem. Because I am a professional learner, I think we're all professional learners, but I make a living by demonstrating how effectively I learn, I take on so much stuff.

Olly: Do you ever find like maybe you spend more time actually talking about how to do it than actually doing it? It seems like an occupational hazard.

Jonathan: Definitely. It's definitely true. I tend to bite off a lot of learning projects, and I used to beat myself up about it.

At any given time, right now I'm…

- learning Russian

- improving Hebrew

- maintaining Spanish

- learning piano and guitar, because one instrument isn't enough and I'm already 30 years behind all these child prodigies who play piano

- acro-yoga

- olympic weightlifting

- aerial photography

- copy writing

- marketing funnels

- advertising

I'm learning like 100 different things at once, and I used to beat myself up about it because of exactly what you said, I should buckle down and talk the talk.

I realized the more I learn, the more I'm able to learn, and that by harnessing exactly that ADD and by jumping from subject to subject, something that I learned in copy writing – that's maybe a bad example, but something that I learned in my fascination with Benjamin Franklin can dramatically alter the way I write copy, and something I learned in Olympic weightlifting can dramatically alter the way that I do acro-yoga.

You kind of have to take advantage – a lot of the techniques that we teach are for taking advantage of that passion and figuring out a way to be passionate about things that you maybe don't actually want to learn, and I've learned that you just have to take advantage of that and roll with it.

Those are some of the things I've been able to learn. I've been able to learn public speaking which, obviously, I use pretty regularly. I've been able to learn – I'll give you a classic example…

Building a Course

October of 2013, I said to myself – I had figured out that this online learning thing was going to be pretty successful, I'd taken some online courses myself and I was like this is a really cool way to distribute knowledge and it's a lot more profitable than writing a book, and it's a lot more engaging, I think this is going to be big.

So, I decided I'm going to build an online course, and I said to myself, “How does one build an online course?” I sat down, I opened 42 browser tabs, and over the course of two days, I knew how to build online courses. I knew how to record video, I knew how to edit video, I knew how to structure the content, I knew what was important, I knew a lot about how these ranking algorithms work on marketplace websites.

Within three weeks of launching, we had one of the best selling courses on Udemy, and within a few months of just doing the stuff that I'd learned over the course of a few days, we had one of the best selling courses of all time.

Olly: For those that don't know, Udemy is an online course marketplace, where you can go and learn pretty much anything. Your course went on to be taken by 60,000 students, is that right?

Jonathan: Up to today, 85,000.

Using Mnemonic Techniques & Speedreading To Learn A New Skill

Olly: Wow, that's pretty amazing. It's interesting hearing you say all these things that you've been able to do, because there's tons of stuff I want to do in my life, I couldn't even begin to name those things. I'd like to learn how to make chocolate, I'd like to be able to illustrate children's books, that's something I thought would be super cool.

Why don't I do that?

The reason is that I don't really have a framework for deciding on and to learn a new skill and taking the action required to do it. I think it's because part of it is the discipline problem for me, but also it's like not having the confidence necessarily that I would be able to learn that skill quite quickly.

On Discipline

Jonathan: That's such a big thing, I want to jump in right there actually, because I just recorded a video about this. One of the kind of beautiful things about what I do is I learn, so I'm always improving.

We've had to redo our course numerous times, and we constantly improve, and over the last year or so in kind of helping students and diagnosing their issue, I've come up with what I call the memory Pygmalion or memory golem affect. So the Pygmalion effect/golem effect are sides of the same coin. I learned about this in that business school program I talked about, if you're a manager and you believe that the employee is highly skilled, intelligent, capable, going to be successful, all things being equal, even if you hide your cards, that employee will be successful.

However, the golem effect, if you believe the employee is dishonest, so on and so forth, you will actually make them dishonest. There's a lot of debate about how this actually works, but it works. People say it's tone of voice, or it's facial expression, or it's subtle little communication cues, whatever it may be – you could call it law of attraction, you could call it energy – it actually works.

What I've realized is the same is exactly true of ourselves. One of the coolest things about these techniques, and I think it's very similar to what you do, is I give students these tools and they use these tools and these tools are really powerful, but guess what, even when they don't use these tools, their memory improves and they become better learners.

How can that be?

They now go around in the world saying, “I'm an exceptional learner, I have a phenomenal memory”. I'll tell you a little secret, I use the actual mnemonic techniques that I teach about 40% of the time, and yet I remember nearly everything. People give me an address, I don't even need to use mnemonic techniques. I could convert it and say that the 77 is a cake and create memory paths, I don't even need to. If I memorize a credit card I might do it, 16 digits, but if I'm memorizing five digit numbers, I don't even need it. It's simply because of this memory Pygmalion effect.

I think so many people go around saying, “I suck at languages, I'm terrible at math, I'm a really slow reader”. Guess what? That is a self fulfilling prophecy. I think the power of these tools is putting that tool in your back pocket so that you can say, “Yes, if I want to go learn chocolate making, that's a one day thing, I can go learn that”.

Olly: Let's dive into some specifics here. From what I've heard, the two main things that you've mentioned are memory improvements or memory techniques and speed reading.

Can you take maybe one of the skills or activities that you've already mentioned and give us an example of how both of those things, the speed reading and the memory techniques could be used to help you learn that thing faster?

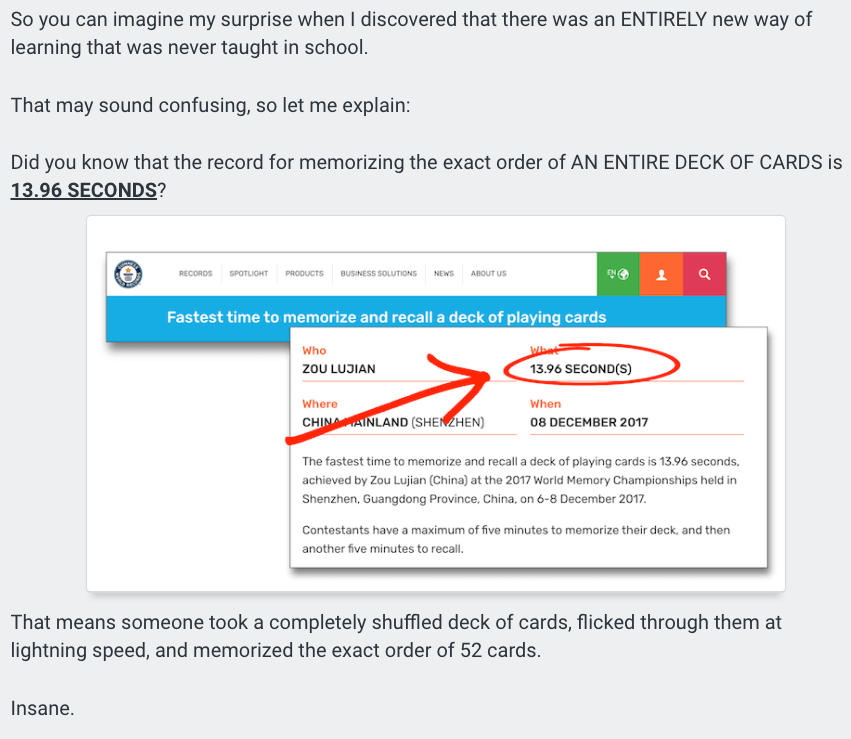

Jonathan: Sure. So, where I think a lot of courses go wrong and a lot of people have tried speed reading, myself included, and failed is they forget to build the infrastructure up front. If you're going to read an entire book in two and a half hours, you better have a pretty incredible way of storing that, and storing it in this auditory, language processing area of the brain is not going to work.

You need to store it in a way that world memory champions store 56 decks of cards back to back, store one deck of cards in 26 seconds, and that's by the same tried and true mnemonic techniques that have been around for 2200 hundred years, with modification and adaptation. It's visual memory, it's creating mnemonic techniques, and then it's the memory palace. If any of these things are foreign to people, I can kind of go into more depth, but it is basically creating these visual mnemonics.

When you pair that on top of speed reading, you're now able to read things very quickly, take a quick pause, generate these very vivid markers and examples. Then it's ultimately deconstructing knowledge into core principles that can be visualized.

How To Retain Information You Read In A Book

Olly: Let's pause right there so I can see if I can summarize what you said. The speed reading, I guess it's fairly obvious, if you've got to learn stuff and you're learning that stuff from a book, you can read it faster if you can read quicker. It stands to reason.

The second part though is actually retaining what you have read. When I was reading about your various courses and talks and things earlier on, there was one phrase out of everything that stood out to me. You know what that was?

Jonathan: Tell me.

Olly: Retain things you read. Now, I guess different elements of this will stick with different people, but for me personally, I get very excited when I read a book. I read slowly, I'm a slow reader. The idea of reading a book in two and a half hours is like how would my life change if that was possible.

You know, I get very excited when I read a book. I've just been reading a great book called Deep Work by Cal Newport, which is very well known at the moment, but as I'm reading that book, I'm thinking to myself by this time tomorrow, I will have forgotten this stuff. I'm going to read this book and enjoy it, get all excited and then not retain it.

So, that's why that particular phrase, retain the things you read, really stood out to me. Could you talk a little bit about the significance of that and how you go about doing that?

Jonathan: I'll back pedal a little bit and talk just a little bit of light neuroscience, specifically evolutionary neuroscience as I like to call it. We're visual creatures. We don't realize it, but – first and foremost, we have to think what kinds of things would provide a survival advantage to homo sapiens wandering the Serengeti for the last one and a half million years.

It turns out smell and taste, super important. If you remember what rancid food tastes like, that's a pretty huge survival advantage. If you remember certain different bitter tastes are poison, that's a pretty big survival advantage.

The next most memorable things are location and visual. Do I remember the markings on the faces of the friendly tribe versus the not friendly tribe? Do you know we can identify someone else's face in about 150 milliseconds?

Why would we develop that, why is that so important? If you take two seconds to identify if I'm a friend or foe, and I take 150 milliseconds, which one of us is going to survive the oncoming battle? So, we remember faces, we remember visual information, the exact shade of the berries that are poisonous, the exact color of the snake that's edible versus the one that's probably going to kill me. We also remember locations.

If you forget where the watering hole is and you're wandering the Serengeti, you're dead. If you forget where you buried your winter food supply, you're dead. So, our brains hold this information.

If anyone doesn't believe me and they say, “Well, I'm not a visual learner, I'm an auditory”, yes, but with this much work, just a tiny bit of work, I can reveal to you that in fact you are a visual, spatial learner just like every other homo sapiens. The test I like to give people is I want you to imagine your childhood home, even if your parents sold that home 20 years ago.

I want you to go into your parent's bedroom and I want you, even if you were one of those kids who were not allowed in Mom and Dad's room, I want you to go to your mother's side of the bed, I want you to tell me what was on the nightstand. You may not have been in that house for 20 years, and I can tell you –

Olly: I can do that.

Jonathan: Exactly. Most people are like it was a red telephone, and I can say, “Was it a touch tone, or was it not?” The funny thing is you can not just do that for highly significant places, but if I asked you about the last hotel you stayed in and I asked you what side of the shower was the shampoo on, you might just know, and that's something that you haven't even reviewed.

So, we do this naturally. To come back to your question in long form, where a lot of people go wrong is they read the words in a book, they hear them as if they were a conversation. Now I want you to ask yourself, I just said something moderately interesting about hotel shower soap, but could you play back the exact words that I said?

No.

The Power of Visualization

Could you go back to that visualization if you stopped to think about that hotel, or could you go back to that image of what's on your mother's nightstand?

Of course.

So, the words themselves are throw away, but the meanings and the visualizations are very much relevant. That's essentially the crux of the technique, if you want to retain what you read, you need to turn it into highly visual, highly imaginative imagery. That's it.

I mean, I can definitely tell you almost none of the words in Benjamin Franklin's autobiography, but I can paint for you of him running through the street with a wheelbarrow three to four times a day with the same bundle of paper, so people would think that he was selling more newspapers. I can tell you the image that I have for this hunta, and I can tell you the image that I have for him getting caught “borrowing” books and why he brought the concept of the public library to life.

Olly: Is this because you are a visual person and you're kind of imagining what it looks like as you're reading? Are you reading the book and then creating that image in your mind?

Jonathan: Yes, we are all visual people.

Olly: Just to finish that, are you – I'm trying to think of the mechanics of how this works. So, you're actually reading something in the book, thinking I want to remember this point, pausing, and then creating and then working on that imagery such that you can remember it. Is that what you're doing?

Jonathan: That's what we teach, is that you create kind of micro pauses when you're flipping a page, try to remember pertinent details, and then at the end of the chapter, you need to go back as you're flipping through those blank pages and review and play back these images and string them together, create a structure.

The truth is that over time, and I can't guarantee that this happens to everybody, it certainly happened to me, over time it just kind of happens. As I'm reading, the images are just kind of cropping up for me. Again, I can't promise that, that happens.

The way that we teach it is take a pause, anyway when you speed read, it's extraordinarily exhausting and most people, though they could theoretically read a book in two and a half, three hours, you've got to take breaks.

So, during those breaks, you get up, you have a glass of water, you start playing back these images, and even if you want to have archival, kind of an index knowledge, you can put them into a memory palace. Although, I don't personally do that. I don't think you need to be able to play back, in order, the points in a Malcolm Gladwell book.

How to Remember Things Quickly Using Structured Repetition Of Ideas

Olly: You know what? It's absolutely fascinating. I'm kind of having a bit of an epiphany as I'm listening to you talking, because – let's see if I can get these thoughts properly structured.

The process you've just described of learning something new in a book, taking note of it, putting your attention on it, carrying on and then coming back to review it later, regular listeners of the podcast will know that this is exactly the way that language vocabulary is acquired. It's a combination of attention and revision, revision in the sense of reviewing.

Jonathan: Spaced repetition.

Olly: I don't know if this is an English word, but I think in America people understand revision to mean changing something, but anyway, I mean reviewing it as in going back to it. So, we've got a combination of putting your attention on stuff and then going back and reviewing it later so that your mind can have another opportunity to better structure it in your head.

I'm seeing all kinds of parallels.

What I hadn't seen up until this point, I hadn't seen those parallels, so I hadn't really considered the fact that information, in exactly the same way as a new word in a foreign language makes perfect sense to you when you've just learned it.

Retaining Information by Tricking the Brain

Then it disappears 30 seconds later, or the next day when you need it in a conversation, I hadn't really considered the fact that information that you read in a book actually behaves in the same way.

When you're reading, you think this is so cool, I didn't know that about Benjamin Franklin, but then you don't have the kind of awareness to think you know what, if I need to remember this tomorrow, I'm not going to be able to do it.

Jonathan: Precisely. Well, I mean our brain has two dedicated centers called the hippocampi, one in the left hemisphere, one in the right hemisphere, and their job is to forget. They are particularly active during sleep, which is why if we don't sleep we become a mess, but the brain is a forgetting machine.

It needs to be, because it already consumes 20% of our energy and resources and oxygen, despite being two percent of the body's mass. It needs to forget to make it as efficient as it is. We pay a lot of prices and a lot of costs for having this massive brain.

The entire reason that we stand up and walk the way that we do is to protect this massive mound of fat, which is by far the most sophisticated super computer known to man.

There are ways to game the hippocampi. If we learn the rules that they abide by, for example they prioritize visual information, they prioritize anything that's connected. So, if you can learn to falsify these connections, and this is the other really big tip to accelerated learning, too many people treat new information as, in fact, new.

They go okay, let me stretch out. Don't know how to play a musical instrument, so everything that I learn about this piano is completely new and foreign to me. What does that tell the hippocampus? It says this is completely irrelevant knowledge, it has no connection to anything that I'll ever learn, or will ever need to learn.

So, basically ~~ shall we dance in Norwegian and they tell you, and you say to yourself this is the only thing that I've ever learned in Norwegian, and your brain goes this is the only thing we know about Norwegian, this must be pretty damn useless, and throws it out the window.

But if you were to say to yourself okay, this is how this is related to this information, this is how I'm going to use this information, you can say this sounds like English except for instead of shall, we say Skoal, and connect it to visual imagery, maybe a tin can of Skoal chewing tobacco.

You create the imagery and tell the brain hey, this is relevant, this is related, this is interesting, new and novel, and then by going back and doing that repetition as you so correctly said, we're telling the brain I just learned this yesterday, but I've already reviewed it once, it must be pretty important.

This information keeps coming up, because your brain doesn't know when you relearn something that it's coming out of an index card or if it's being used in the real world, it has no idea, it just says this phrase, skal vi danse, has come up twice in the last two days, that's interesting.

It must be significant . There are all these different ways, and that's basically all we do, is we trick the brain into determining that things are important.

Olly: Do you think people were efficient learners 100 years ago before radio, TV or internet?

Jonathan: Well, I think about that a lot. A hundred years ago, you would get a book, most likely the Bible, because the printing press wasn't what it is today in terms of low cost, people were actually physically printing books, so there was a high cost associated with books. Literacy rates were not as high, so if you got a book in your hot little hands, you would read that book over and over and over again and be able to cite passages from it.

I mean, even in Benjamin Franklin's day, he set up the first public library in North America and everything, but how many books do you think he really read in his lifetime? Whereas today, we have I believe in the US there's 300,000 new books published each year. In China, I believe it's twice that.

We're completely bombarded with information, so we go wide instead of deep. It's almost really hard to compare, but then you have these guys like Thomas Jefferson, like Benjamin Franklin, who were very sophisticated in many, true polymaths. You say to yourself would we all be like that if we weren't distracted by consuming so much bullshit content, frankly.

Accelerated Learning For Foreign Languages

Olly: Jonathan, you've studied, is it four languages, five languages?

Jonathan: Studied four.

Olly: How did the techniques for how to learn things quickly, that we've been talking about here, help you with language learning?

Jonathan: Great question. As you said for learning vocabulary, these techniques are a game changer. There's no word too difficult, there's no sound too confusing, because I can string words and sounds together and put them into a nice little memory palace with a visual mnemonic, and I almost don't think of vocabulary learning at all as a hurdle anymore, it's just straight into the brain.

I actually made the mistake, when you're a hammer, every problem is a nail as they say, so when I started to learn Russian, I was like 1200 most common Russian words, download them into my flashcard software, create visual images and boom, there we go.

I found myself, I got to about 800 words within a month or two, and then I found the grammar proved to be way more difficult and I found that these words were useless in Russian because if you don't add – it's not like in English where if you say, “Me want eat”, people will understand you.

In Russian, they'll go, “Who wants to eat?” Basically in Russian, if you don't know how to declense the word, not just conjugate but declense, it loses its meaning. You could be working on the computer, or the computer could be working on you and you have no kind of way of knowing that.

So, I've only recently adapted these techniques to learning grammar, and I've kind of figured out a really bizarro way to hack the Russian grammatical system, but at the very least, vocabulary has become kind of a non-issue for me.

Olly: What's the super learner approach to a problem like grammar, which is not just a case of memorizing specific units of information like vocabulary?

Do you approach grammar the same way that you'd approach a book on chocolate making? How do you approach that?

How do you see the problem, the challenge or the opportunity?

Jonathan: What I see it as is a list of rules, and this is maybe not the right way, but this is kind of how my mind thinks. It's a list of rules, so let's take for example in English if it's singular, then the verb becomes pluralized. He wants, he goes, she wants, she goes, you want, you go, that's very strange, but let's go ahead and say they want, he wants.

I need to figure out a way to create that linkage, get those neurons to link together for something that is a bit weird and strange. Why isn't it he want? In other languages – in Hebrew, it's he want, they wants. It makes more sense intuitively, why is that?

So, what I would do is create a visual image to say, for example, grammar is hard and you should never have to go it alone, so I would create this image of this person singularly going, he's going, he goes, but he needs to bring two goes with him.

Maybe it's two arrows, because he shouldn't have to face this grammatical challenge alone. Whereas if they go, they don't need to bring multiple verbs with them, because they're together facing this challenge of grammar.

So, I would just remember that it takes three people or more to tackle some grammar. I just made this up completely on the spot, but I have this visualization of going up against a wall of grammar, and that way I remember it. If it's you, I say you, therefore it's you and I, because I'm kind of the observer, the second person, so we will go and face it together.

So, we can use go instead of you goes. That's just kind of one example where I would say to myself this is how you conjugate. It's basically, it's creating BS meaning, so that I can tell the brain this is how it all links together, then I form a visualization.

Olly: I guess mnemonics – you would call mnemonics BS meaning as well, right? It's just the scaffold or a bridge to get you to the point where your brain can make sense of it enough to retain it, and then that gives you a path back in later when you need to get back to it.

Jonathan: Totally.

The SuperLearner Academy

(Get a free trial here)

Olly: My mind is kind of spinning at the opportunities, mostly for things that I could learn. Not just for – it's not only very, very intriguing the opportunities for language learning, but also I feel like all these – when I think about earlier I mentioned silly things like chocolate making and children's book illustrator, things that I just do for fun, things that I've been putting them off for years, because it's just one more thing.

Stuff that I could do for fun just gets pushed down the list for me, and it's really made me think if I can learn some of these skills quickly and it doesn't have to be a two year undertaking, when I start a new language, I consider it to be a multi-year undertaking, but learning to make nice chocolate, I could learn fairly simple, and it's a question of remember the steps, remembering the baking temperatures and all that.

So, I'm super inspired, and I'm feeling good. What can I say?

You run the SuperLearner Academy, this is where you teach, this is where you do your work, and this is where you teach the accelerated learning skills that we've been talking about today. Tell us about that. Who should consider it, what's involved, what do you learn?

The Superlearner Masterclass

Jonathan: So, about a year and some change ago, we decided that we wanted to create the absolute finest accelerated learning program that money could buy. The result was something that we call the Superlearner Masterclass.

It's a 10 week comprehensive program, you can go through it faster, you can go through it slower, but paced out at about 30 minutes a day, four to five times a week, it is about 10 weeks. A lot of that 30 minutes is hey, you're going to read your emails, you're going to read the newspaper, do it in this specific way.

So, it's not all watching videos and stuff like that, I don't expect anyone to watch that many videos of me. Essentially what it is, is it starts with a very strong core understanding in memory and mnemonic techniques.

So, all these things that I told you about; how to memorize information, numbers, names, how to store your information long term, how to review it, or as you said revise it in a way that is going to allow you to remember it forever, because no amount of mnemonic technique is going to put it in your brain forever. You have to kind of be intelligent about the intervals in which you review and how you review.

Speed Reading

Then it goes into speed reading.

So, it's about 70% memory, 30% speed reading. Once you have that infrastructure, you can then go on and learn anything, and most of what you're going to want to learn is, of course, in books, although we do talk a little bit about how do I take on a challenge like Olympic weightlifting, for example, which cannot really be learned in books, and how do you take on a challenge like acro-yoga, which definitely cannot be learned in books.

That's it. It's essentially a comprehensive program. Of course, we offer a free trial if people want to check it out, where they can sign up, no credit card required, and do the first entire module of the course.

So, diagnose their reading, diagnose their memory, start to understand some of the fundamentals, download all the worksheets, set their goals, set their progress, understand exactly what the hell I'm talking about throughout the course, and really set themselves up. Then if they want to, they can always upgrade and unlock the other, I believe it's eight more modules or nine more modules.

Olly: That's great, so you can take the time to get a feel for it. Certainly what struck me when I went through the course was the quality of the production. You must have really put your heart and soul into creating this, the quality – I've never seen anything like it.

Jonathan: Thank you. As you can see, if people are watching the video, I really believe in super high quality. In fact, we've now invested in a studio of our own, this studio that I'm in now. I look back on those videos and I'm like we've got to clean up the audio, we've got to do this, because we're always trying to push the bar.

If I can get to a point where it's as close to being in the room with me in terms of quality, that takes that whole distraction of echo in the room, or blurry camera out of the way and allows the student to really focus in on the content. It's like if a car is smooth enough, you almost forget you're riding on a bumpy road, and that's what I want people to experience.

Olly: Wonderful. Well listen, it's been such a pleasure to talk to you today, I learned a lot as always. If people want to get in touch with you, where can they do so?

Jonathan: So, they can check my personal website at jle.vi. They can check out my podcast at BecomingASuperHuman.com. We've had such illustrious guests as Mr. Olly Richard on this show. (Click here to listen to that episode!)

Olly: That was a fun episode, that was a good chat.

Jonathan: That was really fun. People really enjoyed it as well. I assume you'll give them a link to get access to that free trial.

Olly: Yes, we'll tell people where to go for that. Lovely. Well, thanks very much, and I look forward to the next time, and we'll talk very soon.

Learn how to remember things quickly with a free trial of the Jonathan Levi SuperLearner Academy: Click Here

Olly Richards

Creator of the StoryLearning® Method

Olly Richards is a renowned polyglot and language learning expert with over 15 years of experience teaching millions through his innovative StoryLearning® method. He is the creator of StoryLearning, one of the world's largest language learning blogs with 500,000+ monthly readers.

Olly has authored 30+ language learning books and courses, including the bestselling "Short Stories" series published by Teach Yourself.

When not developing new teaching methods, Richards practices what he preaches—he speaks 8 languages fluently and continues learning new ones through his own methodology.