Every day, I talk to people who have the wrong idea about language learning.

Some of these myths and misconceptions about second language learning are so powerful, that they actually prevent you from learning your target language.

In this post, Arkady Zilberman, a simultaneous translator and founder of Language Bridge, is going to look at some of these myths about language learning.

Now, I don't agree with everything Arkady says.

But I do love encouraging a healthy debate on language learning!

So in that spirit, let's get into it.

Here are the 5 misconceptions Arkady will cover in the post:

Myths about language learning

- You must learn a foreign language as you would learn any academic subject

- The best method of learning English is traditional classroom teaching

- The next best method is to watch videos in the new language

- Language exchange websites are a useful learning aid

- Use flashcards to build up your vocabulary

Pro Tip

If you want to be a successful language learner, using the right method is key.

My courses teach you through StoryLearning®, a fun and effective method that gets you fluent thanks to stories, not rules. Find out more and claim your free 7-day trial of the course of your choice.

Enter Arkady…

Myth 1 – You must learn a foreign language as you would any academic subject

We spend years in school learning a lot of subjects.

Schools teach most subjects using textbooks, lectures, notes, memorization, and tests. The only problem is that language skills cannot be learned in this way, any more than you can learn to play the guitar or drive a car by reading or even memorizing its instruction manual.

You acquire a language by actively engaging with it until its essence, not just its rules, is familiar and natural to you.

You use a language to communicate.

When you are in a real-life, real-time conversation, there is no time to think about grammar or sentence structure, or to access your knowledge database.

Because the education system continues to try to teach languages by measurable outcomes (how many words you have memorized and how many grammatical rules you can explain) rather than how well you can communicate when you really need to, the failure rate for the traditional method is absolutely appalling.

Despite the failure of most “successful” students to speak the foreign language fluently, schools continue to use their traditional methods.

We need to create a new approach based on acquiring language skills, not on learning rules or lists of words.

There are many definitions of skill.

I prefer this one:

Skill is proficiency, facility, or dexterity that you acquire or develop through training or experience.

We know many teachers have helped people acquire foreign languages by following the recommendations of Dr. Stephen Krashen.

In 1982 Dr. Krashen described the acquisition method:

Language acquisition is a subconscious process; language acquirers are not usually aware of the fact that they are acquiring language, but are only aware of the fact that they are using the language for communication.

The result of language acquisition, acquired competence, is also subconscious. We are generally not consciously aware of the rules of the languages we have acquired.

Instead, we have a “feel” for correctness. Grammatical sentences “sound” right, or “feel” right, and errors feel wrong, even if we do not consciously know what rule was violated.”

Dr. James Asher, founder of the Total Physical Response (TPR) system, has thousands of followers whose experience shows the efficiency of TPR – a special version of the acquisition method.

Implementing a program for adults of acquiring a language encounters two main barriers, which explain why the acquisition is not a leading method in the language market:

- The existing system of teaching foreign languages, and evaluating students, is one of the biggest second language acquisition myths. Changing the system would require retraining the teachers, which would be costly even if all the teachers were enthusiastic and motivated.

- Even radical teachers who would like to experiment with the acquisition method would need an application for mobile devices to help adult learners acquire a foreign language 24/7. There are no such applications on the market so far.

There are other challenges to replacing the traditional grammar-translation learning method with language acquisition, but if we solved these two we have made the transition possible.

Language Bridge Technology (LBT) offers a detailed method of teaching a learner how to acquire foreign language skills, and also an Android application for self-teaching English by adults. This application could be also used in instructor-guided learning.

To acquire a language effectively you must retrain your mind, tongue, and hearing at exactly the same time, because they must work together when you speak the new language.

The proprietary Reverse Language Resonance (RLR) process makes this retraining possible.

RLR activates the left and right brain and enables the subconscious component of language learning called priming implicit memory. RLR uses word clouds and relaxing music while exposing the learner to the words being introduced in a lesson.

Exposing the user to a word cloud of the new words in the lesson before the user goes through the lesson has a long-lasting effect, even if the learner has no conscious recollection of the word cloud.

The exposure facilitates spontaneous acquisition of a lesson in a foreign language.

The priming process of implicit memory, invoked through listening to relaxing music while viewing the word cloud, helps the learner recognize the lesson's new words as familiar, and they more easily transfer to the learner's conscious memory while the learner is performing the RLR process.

Instead of this misconception, we say…

A foreign language is not a subject you learn: it is a skill you acquire.

Myth 2 – The best method of learning English is traditional classroom teaching

Currently, there are 1.2 billion learners of English as a foreign language (EFL) in the world; it means that we can’t meet this unprecedented demand using only teachers trained in the conventional methods.

The only other option is integrated learning.

Integrated learning is a combination of self-teaching using web-apps or apps on a smartphone, and online or offline classes with teachers who use the acquisition of EFL skills; the same method that is used in self-teaching applications.

There are 400 million EFL learners in China, and 100,000 native English speakers teaching English, and the 3,000 or so companies offering English classes cannot meet the demand of every fourth Chinese person wanting to learn English.

(A fascinating coincidence: 25% of the global population speaks English and 25% of China’s population is learning English.)

Conventional methods of teaching EFL are passive. In a language class of twenty students, each student participates in active conversation of no more than one and two minutes per session.

The remaining time is passive listening to the teacher’s explanations or other students’ conversations. This explains the low retention rate.

How can we increase the time of active conversation in a class for each student?

By introducing Integrated Teaching, LBT enables the time of active conversation in a class for each student to increase 5- or 10-fold. Instructors who are not native speakers in the new language can present Integrated Teaching, thus increasing the pool of possible teachers.

The ratio between self-teaching and trainer-led instruction ranges between 10% and 90%, depending on the learners' access to language classes.

The learners' active time of speaking in English is 5-10 times higher than in a conventional class, due to speech shadowing of pre-recorded lessons, which all students can do at the same time.

Digital Learners require a student-centered approach and integrated learning, in which a teacher plays the role of a coach, guide, or facilitator.

The LBT application runs on the digital learners’ tablets and smartphones, and integrates with the social media programs every learner uses many hours a day.

Access to the application motivates the learner to continue acquiring the language outside of formal class sessions. The method and the application reinforce acquiring the language rather than learning facts about the language.

Instead of this misconception, we say…

Acquiring a language requires an integrated method.

Myth 3 – watch videos in the new language

I offer a simple experiment: watch a ten minutes video on YouTube, then the next day relate the video to somebody.

You will be surprised to notice that, although you will be able to tell the main story or the theme of it, and your reactions and feelings, you will not be able to repeat the words used in the video.

In contrast to a video, text requires our full attention in order to assimilate the information presented.

We are accustomed to multitasking: we divide our attention to perform various tasks concurrently. Watching a video lesson is a passive operation and it would be hard for us to pay full attention to the words used in the video since, in the competition for attention, visuals and feelings always win.

If we watch videos regularly, we probably do something else at the same time—we remember our last meeting, send text messages, or talk with others in the room not about the video but about recent events.

So while the video can deliver the shape and feel of a story powerfully, there is little chance that you would acquire new words or expressions from the video—not in a way that would allow you to use them later.

Since a video does not allow the inclusion of support in the native language, it is hard to make it understandable to adult learners.

Another disadvantage is that novice language learners usually don’t hear the particular sounds that the new language has but their native language doesn’t have.

Students need special tools that will help them first recognize, then imitate and finally produce sentences in the new language with pronunciation close to that of native speakers. Video lessons cannot help students achieve this objective.

According to the Learning Pyramid we remember about 50% of what we hear and see (which includes watching a video), and 75% of what we are doing.

With LBT’s main drill, learners repeatedly perform speech shadowing and pronounce everything they see, read and hear. Video lessons are passive learning, whereas speech shadowing is active learning.

The fact that millions of people use video lessons and that thousands of websites offer them does not prove their validity for learning English.

We have a very high failure rate of learning a foreign language in the world and need to evaluate carefully the conventional methods since evidently they are responsible for the current situation in the language market.

In response to this misconception, we say…

Video lessons are not the best language learning resource.

Myth 4 – Language exchange websites are a useful learning aid

Kirsten Winkler, in “Language exchange relationships are complicated”, gives the best explanation of why language exchanges do not work.

Kirsten illustrates why language exchange websites might actually never take off and some of the issues around language exchange.

Most likely, neither of the two partners is a professional tutor as in this case the learner could have taken lessons with a teacher or tutor right from the start. Learning a language requires a framework and structure.

In most cases, you will achieve this with a professional person who does that on a daily basis and for a living.

Can language exchange work at all?

The main issue I see is that language learning has a clear hierarchy: one is the teacher and one is the learner. There are mental barriers to switching roles in the middle of the conversation or at the next meeting.

Therefore, you cannot learn and teach in the same pair.

You need to have one partner as your teacher and another whom you teach. In language exchanges the social relationship (either good or bad) takes on more importance than the activity.

Neither side is as interested in the other as they are interested in themselves. Most people are subconsciously looking to get more out of the relationship than they put into it.

To turn websites for language exchange into something more appealing and practical we need to change the framework and structure of the platform.

It should be accessible from a mobile device and offer both a Learning Environment and a Student Hangout.

The Learning Environment should incorporate new learning techniques with step-by-step instruction for self-teaching and for guided learning.

Traditional websites offering a language exchange option (for example, My Language Exchange, Interpals) view these as separate stages. Personal interactions, making new friends, and informal practice of language skills learned should take place in the Student Hangout.

We respond to this misconception with:

Websites for language exchange rarely are helpful in improving language skills.

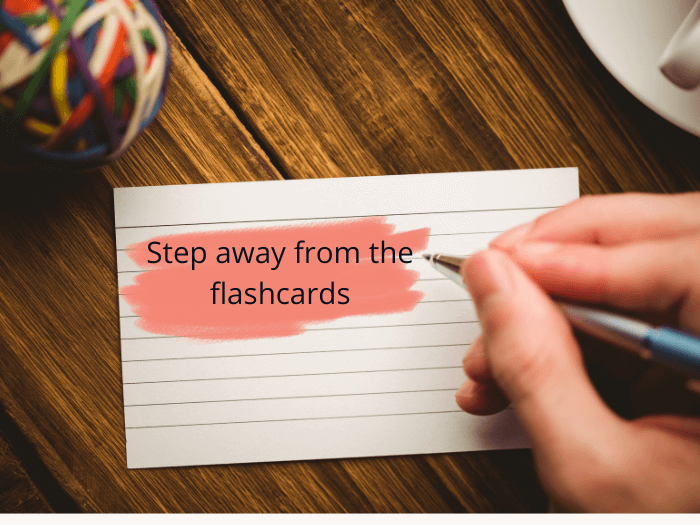

Myth 5 – Use flashcards to build up your vocabulary

Language is not information to be remembered.

It is a skill you develop with training and practice.

Flashcards were invented for remembering information and are still used for that purpose.

I agree with Randy the Yearlyglot who wrote:

“I know that this post is going to upset a lot of people. Stop using flashcards. Stop using SRS (Space Repetition Systems). Stop learning vocabulary from lists, or decks, or programs. Stop it. It doesn't work; it's a waste of time, and it's creating bad patterns in your brain.

There are two things that make flashcards bad.

And I don't just mean bad as in “ineffective”—I mean bad as in “working against you”. Learning anything (words and phrases) alongside its translation is creating extra steps in your brain. It makes you think slowly, hear slowly, and speak slowly.

Here's an example. I'm learning Italian this year.

Let's assume that I learned Italian vocabulary from flashcards. I might have a card that says “vedere” on one side, and to see on the other. Learning this way forces my brain to associate the word “vedere” with the words “to see”.

But flashcards encourage you to believe in one-to-one translations. They make you narrow-minded and unaware of the language you think you're learning.

When you learn a foreign word and an English word together and burn them together into your mind as a pair, you create the illusion of a world where every language is exactly the same, just with different words.

However, that world doesn't actually exist.

“To see” in English can mean what you do with your eyes, what do you when you finally understand something and even a bid you can make when you're playing poker.

“Vedere” in Italian can mean what you do with your eyes, consulting someone, grasping something, verifying something, and so on.

They are not quite the same, and if every time you think you want to use “vedere” you have go through an internal verification process (“Oh, right: maybe not the poker thing”) you will speak very slowly and stiffly.”

Memorizing with the aid of flashcards can help you learn the names and concepts you need to know for almost any subject, such as law or anatomy.

But knowing the names and concepts would not be enough to prepare you to plead a case in court or operate on something. You would need to acquire the skills of an attorney or a surgeon.

Language is not information to be remembered.

It is a skill to be acquired by your brain while speaking the new language.

If you want to speak English you must—speak English. You do it very badly at first, and perhaps not really understanding what you are saying. But the act of speaking develops language patterns in your brain that, bit by bit, make English something you don't have to struggle with, but a language you can use to convince, to amuse, and to inform others.

Using flashcards can work against you if you are pursuing the acquisition of language skills.

Most adults, when learning a foreign language, subconsciously revert to cross-translation to and from their mother tongue.

Cross-translation is the main barrier most teachers ignore.

When you cross-translate, you think in your native language while trying to speak in a foreign language.

Children do not have this problem and acquire any language in their environment subconsciously by forming direct links from images and concepts to words and phrases in the new language.

So every language that a child learns becomes native to him. Children preserve this ability until about 12 years of age.

It is worth bearing in mind that even if the teaching is in the target language exclusively and formally, with no translation drills in class sessions, most adults (about 95%) still revert to subconscious cross-translation.

Your speed of talking in the new language is an easy check. Your normal talking speed in your native language is probably between 90 and 130 words per minute. If you speak the new language in short sentences with a speed of about 60wpm, it is a sign you have a cross-translation problem.

You are constantly reverting to your mother tongue when trying to express your thoughts in a foreign language, although you are not aware of this process.

Cross-translation is the main barrier in acquiring fluency in a foreign language, and flashcards will reinforce that barrier. In acquiring skill in a language, there is no place for flashcards if you want to not only read, but to speak and engage in conversation.

We speak in our native language automatically, producing about two words a second.

Conscious remembering is a very slow process that can slow your speaking rate so much that the person you are speaking with may forget what was at the start of your sentence.

To speak fluently a learner needs subconscious training by practicing words that habitually appear together and thereby convey meaning by association.

To the last of the myths about learning a second language, we say…

Avoid flashcards when acquiring language skills.

In Summary

These five myths about language learning have their roots in the big misconception that you can teach a language the way your teachers learned it – by the traditional grammar-translation learning method.

We need to replace the traditional method of learning a foreign language with language acquisition or training language skills.

In summary, here are five statements to counter the five misconceptions:

- A foreign language is not a subject you learn: it is a skill you acquire.

- Acquiring a language requires an integrated method.

- Video lessons are not the next-best language learning resource.

- Websites for language exchange rarely improve language skills.

- Avoid flashcards when acquiring language skills.

Thanks Arkady!

There were some great arguments in this post.

Whether you agree with them or not, thinking about these issues is exactly what helps you become an independent learner, confident of the method that works for you.

So – what do you think?

What do you agree or disagree with, and why?

Let me know in the comments!

Image: burningmonk

Olly Richards

Creator of the StoryLearning® Method

Olly Richards is a renowned polyglot and language learning expert with over 15 years of experience teaching millions through his innovative StoryLearning® method. He is the creator of StoryLearning, one of the world's largest language learning blogs with 500,000+ monthly readers.

Olly has authored 30+ language learning books and courses, including the bestselling "Short Stories" series published by Teach Yourself.

When not developing new teaching methods, Richards practices what he preaches—he speaks 8 languages fluently and continues learning new ones through his own methodology.