Today I'm delighted to feature a guest post by Luke Truman about how to learn Cantonese from scratch.

Whether you're new to Cantonese or you've been learning for a little while, there's a tonne of great information here that you're sure to find helpful!

WARNING: Because the aim of this post is to be as comprehensive and helpful as possible, it's pretty long! So I've prepared a special free PDF version of the article that you can download to read anywhere, anytime. It’s completely free to download; simply click here to grab your copy.

Ok, over to Luke…

Learning Cantonese may seem intimidating at first.

But if you know exactly how to go about learning as a beginner, and how to break the task down, this whole process becomes a lot easier.

When you first start out, the words will sound unfamiliar and the writing system will seem like a bunch of scribbles.

But if you persevere, you will open up a whole world of opportunities to live your life the way you want to, with Cantonese at the centre of it. You will be able to impress your friends, watch dramas from Hong Kong, engage with locals and much more.

I speak honestly, when I say learning Cantonese has changed my life.

It has opened up so many doors for me that I never even thought possible when I started. And I know that learning it will be a life-changing experience for you too.

It’s not just the final results that are worth the effort. The whole process of learning and discovery with Cantonese is one of the most rewarding and enriching things you'll ever do.

In this post, you’ll discover exactly how to learn Cantonese as a beginner. I’ll provide a roadmap so you can avoid all of the common beginner mistakes and pitfalls and jumpstart your journey to Cantonese fluency today.

Here’s what we’ll cover. If you’ve ever asked yourself any of the following questions, then this article is for you. If you want to skip ahead, just click the section that interests you.

- Why Should I Learn Cantonese?

- What Are The Key Features Of Cantonese?

- What Do I Need to Know About Cantonese Grammar?

- How Should I Approach Reading And Writing In Cantonese?

- What Pitfalls Do I Need To Avoid As A Beginner Learner?

- What's The Best Way To Best Way To Become Fluent In Cantonese?

- What Are The Best Resources For Learning Cantonese?

Remember, you can download a free PDF of this entire article, so you can download it and read it anywhere, anytime. Click here to grab your copy.

Why Should You Learn Cantonese?

“Why Cantonese?” you might ask.

“Why not something more universal like Spanish or French that’s spoken in countless countries around the world?”

Let’s find out…

For a start, Cantonese is probably more widely spoken than you think.

It’s a member of the Chinese language family spoken in Hong Kong, Macau, parts of Malaysia, and southern China, with almost 60 million native speakers.

Not to mention there are a staggering number of Chinese communities around the world, especially in the United States and the UK, where people speak Cantonese.

Cantonese Culture

The Cantonese language also has a very rich culture, with Hong Kong at the hub.

Let’s consider some of the incredible cultural benefits of learning Cantonese:

1. Hong Kong cinema is legendary – featuring names like Bruce Lee, Jackie Chan, IP man, Stephen Chow and many others, Cantonese cinema is popular all over the world. Personally, my favourite movie has to be Shaolin Soccer (少林足球 siu3 lam4 zuk1 kau4). The first time I watched this film, I was in tears with laughter. This Kung Fu style comedy became a signature feature in all of Stephen Chow’s films and Shaolin Soccer will keep you laughing the whole way through.

2. Incredible Hong Kong TV Dramas – Hong Kong is also famous for its world-class dramas. My personal favourite drama is No Regrets (巾幗梟雄之義海豪情 gan1 gwok3 hiu1 hung4 zi1 ji6 hoi2 hou4 cing4). This gripping story is based in WW2 China as the Japanese are invading. You can see an interesting power struggle between the police, the drug lords and how everything changes as the Japanese invade. Another famous Cantonese drama is A Journey To The West (西遊記 sai1 jau4 gei3), which is based on one of the four great Chinese novels and has gone on to influence media in Japan and other countries too.

3. Toe-Tapping Cantonese Tunes If you’re more of a music fan, you can delve into the world of Canto-pop, and listen to some of the genre’s classic songs. The Cantopop genre includes everything from classic rock [“Beyond” (海闊天空 hoi2 fut3 tin1 hung1)], to a more traditional pop style [“Someday I’ll Fly” by G.E.M.], so there's something in it for every music fan.

4. The City of Hong Kong On top of that, you can explore the city of Hong Kong itself, taste the local Cantonese food, and speak with local people! Cantonese people are very happy to hear when foreigners choose to learn Cantonese instead of Mandarin and speaking Cantonese will be sure to enhance your experience should you ever visit Hong Kong or Macau.

Key Features of Cantonese

In this section, we’ll look at the key linguistic features of Cantonese and what they mean for you as beginner learner. You’ll learn about:

- Cantonese Characters

- Cantonese Tones

- Homophones In Cantonese

- Spoken Cantonese vs Written Cantonese

- The Lazy Accent In Cantonese

- Cantonese Romanisation Systems

- English Root Words & Load Words

The Cantonese Character System

Cantonese, like every Chinese language, uses a character-based writing system, where each character corresponds to a block of meaning, not a sound.

There are two main types of characters, traditional and simplified.

This is because, in the 1950s, the state council of the People’s Republic of China simplified a large number of characters in an effort to try and boost literacy rates.

Nowadays, the simplified system is the most common one throughout mainland China.

However, areas outside the mainland such as Hong Kong, Macau or Taiwan still use the traditional set.

Unfortunately, for some of the characters, this simplification meant a loss of meaning.

Take a look at this example, meaning “love”:

- 愛 (oi3) [Traditional]

- 爱 (oi3) [Simplified]

Look carefully at the simplified character (on the right) and you’ll see that it is now missing the component for “heart – 心 -, which is included in the traditional equivalent.

Typically, people from Hong Kong or Macau would use the traditional set of characters, and people from mainland China (Guangdong) would use the simplified versions.

Almost all Cantonese material comes from Hong Kong.

Therefore if you want to learn Chinese characters for Cantonese, the traditional system is by far the best option.

However, as a beginner, this isn’t something you should worry about too much.

You can get up to a comfortable conversational level without ever touching characters at all.

It is only at the intermediate and above stages that it will start to hinder your progress.

Cantonese Tones – What Are They?

Cantonese is a tonal language.

This is something it has in common with all other members of the Chinese language family, as well as Thai, Vietnamese and many others.

But what is a tone?

If you’ve never studied a tonal language before, you probably have no idea what this even means!

In tonal languages, a word’s meaning changes based on the pitch or intonation you use when you say it, as well on as the letters themselves.

For example, each of the following characters represents a different word in Cantonese.

Even though they use the same syllable, the pitch of the speaker changes their meaning:

- 試 (si3) – Here with the third tone, this means to try

- 史 (si2) – The same sound with the second tone, means history

This may sound completely alien to you but we actually use intonation a lot in English too.

For example, to indicate that something is a question we add a rising intonation to our speech.

Think about the following sentence in English and how the intonation alters its meaning:

- You’re not going to the cinema with Lucy tonight.

- You’re not going to the cinema with Lucy tonight?

- You’re NOT going to the cinema with Lucy tonight!

The first sentence, without any stress on any particular word, is simply a statement of a fact.

In the second variation, we change the pitch and intonation slightly, which turns the same words into a question rather than a statement.

And in the third variation, by stressing the word “not”, we turn the sentence into a demand, forbidding the person to go to the cinema with Lucy.

The only difference in Cantonese is that the change in pitch or intonation directly changes the meaning of the word, not the inflexion.

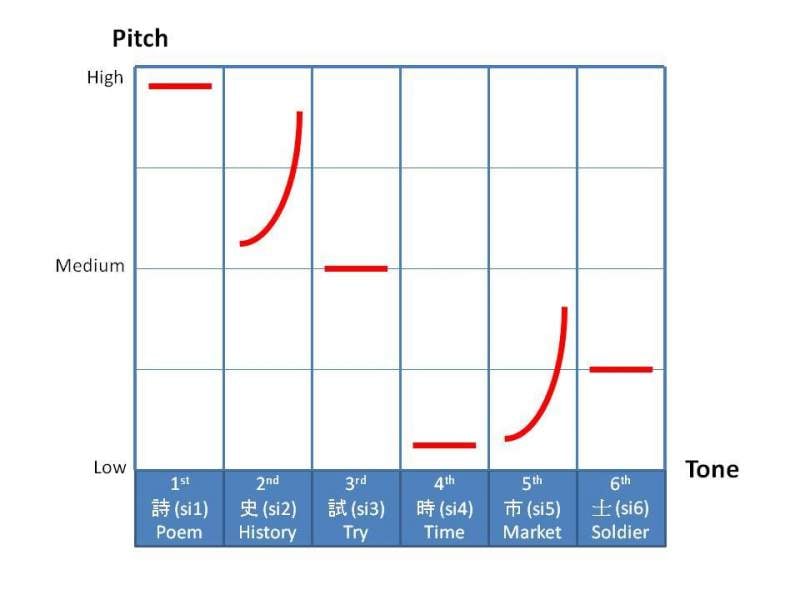

The 6 Tones Of Modern Cantonese

If you ask native speakers they will tell you that Cantonese has 9 tones and that it’s impossible for foreigners to master them.

This puts a lot of learners off before they even start, but actually, over the years some tones have merged, and now only 6 tones are taught in modern Cantonese.

So what are the 6 tones in Cantonese?

At the bottom of the diagram above you can see how each of these tones is applied to the syllable si.

As you can see, when you change the pitch, the same syllable si has a different meaning. It also sounds quite different in each case. Have a listen:

- Tone 1

- Tone 2

- Tone 3

- Tone 4

- Tone 5

- Tone 6

This combined with the fact that Cantonese has a lot of homonyms (words with the same sound & tone but with different meanings) and the fact that the sounds are quite short, makes listening very difficult at first.

But don't worry – your ear will adapt to the sounds of Cantonese with time and practice.

Homophones In Cantonese

Another key feature of Cantonese to be aware of, as with any Chinese language, is the massive amount of homophones present.

Homophones are different words that have the same sound but different meanings or spellings.

As native speakers of English, we are already familiar with this concept through English homophones like “too”, “two” and “to”.

In Cantonese, there are a lot of words with the same sound and tone, but with different meanings.

The key to distinguishing the difference between these words is through context.

Because of this, distinguishing homophones will get easier and easier with time as your vocabulary grows.

Let’s look at some examples.

- 林 meaning forest

- 淋 meaning to pour

Both are pronounced as “lam4”.

The Key To Understanding Homophones Is Context

However, because most Cantonese words come with two characters it is unlikely you will hear them in isolation. This makes figuring out the meaning from context a lot easier than English.

For example, in the full word for forest 森林 (sam1 lam4), you will know from context what the meaning is.

An example using the character for pour would be in the phrase 淋濕 (lam4 sap1) meaning to get soaked.

Another point which makes our lives easier is that in the majority of cases the homonyms are so rare and underused that even a lot of native speakers won’t know all of them!

This makes it incredibly easy to know which one is being used as it will probably be the only one you know.

Spoken Cantonese vs Written Chinese

When I first started to learn Cantonese I kept on trying to use words I found either in my dictionary or my beginners’ resources.

But native speakers kept on telling me: “No, that’s the written form. We don’t say it like that”.

This confused me because I really didn’t understand the difference between the spoken and written form.

I didn’t know why when people write things down they use a different form to what they say colloquially.

In reality, the reason is very logical.

Because China has 300+ languages/dialects, it was necessary to create a standard writing system in order to allow people from all over the country to communicate with one another.

This standard writing system was created based on the national language – Mandarin Chinese.

This is what’s known as standard written Chinese.

In essence, all formal documents and serious literature will be written in standard Chinese as this allows it to be read and shared all across China.

Is There Such A Thing As Written Cantonese?

If the material is written colloquially in spoken Cantonese, only Cantonese speakers would be able to understand it.

This can be a little confusing at first, but in essence, if you use written Chinese, you are essentially speaking Mandarin with a Cantonese pronunciation of the characters.

So does that mean Cantonese is never actually written down?

No, not at all!

Spoken Cantonese is commonly used for texting, on blogs and in comments on the internet.

It’s also popular in comic books and for the subtitles of movies and YouTube videos.

There have also been several books in Cantonese written and published on the Hong Kong golden internet forum (which is like a Hong Kong version of Reddit) that you can access for free.

As a beginner learner, trying to learn the spoken and written form at the same time, while keeping them separate in your head is difficult.

Therefore, I strongly recommend focusing all of your attention on the spoken form of the language first, and then you can always revisit the written form at the more advanced stages.

The Lazy Accent In Cantonese

Another thing that confused me a lot when I first started learning, was the fact that Cantonese words with “n” sounds, can also be pronounced with an “l” sound.

I would learn words like 呢 (ni) meaning “this”, or 你 (nei5) meaning “you”, and then when it came to speaking with natives not recognize them in conversation because they are pronounced differently.

Most natives would colloquially pronounce the “n” as an “l” sound.

This is what’s called “the lazy accent“.

So, the examples above would end up being pronounced like li1 (呢) or lei5(你) instead of 呢 (ni) and 你 (nei5).

The two sounds can be used interchangeably, but words that originally have an “l” sound, cannot be pronounced with an “n”.

For example 嚟 (lai4), meaning “to come”, can not be pronounced as “nai4”.

The good thing to know here is that most Hong Kongers use the “l” sound.

If you are in doubt about which one to use, the “l” sound works in every situation, so you can’t go wrong!

Cantonese Romanization Systems

Another key feature of Cantonese (at least for learners) is its romanization system.

First of all, what is a romanization system?

It is a learning aid, in order to help foreigners learn a language that doesn’t use a Latin alphabet.

Because the Cantonese characters themselves stand for blocks of meaning, and are not phonetic, looking at a character and knowing its meaning doesn’t mean you are going to be able to say it!

So romanization systems are designed to help as a pronunciation guide.

They can also act as an aid in learning material when you are trying to pick out sounds from a transcript.

What’s more is that there are over 50,000 Characters in Cantonese, and they seem intimidating at first.

Using a romanization system allows you to bypass characters at first, learn to speak and build up your confidence, and then tackle characters further down the line.

Jyutping vs. Yale

There are two major romanization systems in use now for Cantonese:

- Jyutping

- Yale

Jyupting uses numbers after the words to mark the tone.

Yale uses accents to mark the tones, with the addition of an “h” for the lower register sounds.

For example, the word 用 meaning “to use” is written as:

- jung6 (Jyutping)

- yuhng (Yale)

Notice how the “J” of Jyutping system is replaced with a “Y” in the Yale system, and how an “h” is added to indicate the low pitch.

There are no tone lines here, so you know it is flat in pitch.

Another example is the word 好, meaning “good”. It is written as:

- hou2 (Jyutping)

- hóu (Yale)

In this example, the second tone is not in the low register so there is no added “h”, and the upward mark above the letter “o” shows the rising tone.

Both Jyutping and Yale are pretty easy to get used to, as they are designed for ease of use by a native English speaker.

That being said, it’s a good idea to check what resources you want to use, and try to buy products that use the same style of romanization to avoid confusion or mixing up sounds.

In general, older material, such as Teach Yourself Complete Cantonese uses Yale, where most newer material favours Jyutping.

It is for this reason that I would strongly recommend starting out with Jyutping, and this is why I have used Jyutping as the romanization system in this guide.

English Root Words & Loan Words

As you may be aware, Hong Kong was originally a British colony until it was handed back over to China in 1997.

Because of over 100 years of British rule, both British culture and the English language have had a huge impact on Hong Kong and on the Cantonese language.

This means that Cantonese features many English loan words.

There are two types of English loan words in Cantonese.

Firstly, there are words copied over from English that use close matching characters so that the words sound relatively similar to English.

These are usually incredibly easy to remember. Let’s call these English root words.

Let me give you a few examples:

- 貼士 (tip1 si2)

- tips/advice

- 波士 – (bo1 si2)

- boss

- 士多啤梨 – (si6 do1 be1 lei2)

- strawberry

These words are all very similar to English, and actually, there are a lot more of these than you might think.

But that’s not all!

There is another kind of English loan word that make Cantonese even easier…

Words That Are The Same In English And Cantonese

Because of the heavy British influence in Hong Kong, many English words have been adopted into modern Hong Kong Cantonese without changing at all!

In fact, it has gone so far I have heard people say if you can’t remember a word, just say the English word and there is a good chance it will be perfectly acceptable anyway.

Let’s look at a few common examples in context:

- 佢係我嘅 Friend 啦 – (keoi5 hai6 ngo5 ge3 Friend laa3)

- He/she is my friend

- 我啱啱send咗message比你 – (ngo5 ngaam1 ngaam1 send zo2 message bei2 nei5)

- I just sent you a message

- 幾時你想食lunch呀? – (gei2 si4 nei5 soeng5 sik6 lunch aa3?)

- When do you want to eat lunch?

As you can see these words have not been changed from English in any way, and there are a lot more of these than you might think giving you quite a few freebies when you first start learning.

The Basics Of Cantonese Grammar

One of the things about Cantonese that is easier than in European languages is its grammar.

In fact, the basic grammar of Cantonese is quite simple.

In this section, you'll learn about some of the key aspects of Cantonese grammar and why they might be easier than you think!

- Expressing Time In Cantonese

- Particles

- Asking Questions In Cantonese

- Cantonese Measure Words

- The Number 2 In Cantonese

Expressing Time

Cantonese has no genders and no verb conjugations.

But if there are no verb conjugations, how is time expressed?

In order to express when something happened, a time phrase is used at the start of the sentence alongside something called a particle, which goes after the verb.

- 噚日我去咗公園 – (kam4 jat6 ngo5 heoi3 zo2 gung1 jyun2)

- Yesterday I went to the park

- 而家我去緊公園 – (ji4 gaa1 ngo5 heoi3 gan2 gung1 jyun2)

- I am going to the park now

- 聽日我會去公園 – (ting1 jat6 ngo5 wui5 heoi3 gung1 jyun2)

- Tomorrow I will go to the park

So let’s break down what’s happening here:

- Notice how the verb, 去 (heoi3/ to go) remains unchanged in all three examples.

- To express the past tense, the particle 咗 (zo2) is used after the verb, and this shows that the action was done in the past. This is the same no matter what verb you use.

- To express something that is happening right now, the particle 緊 (gan2) is used after the verb.

- And to express something that will happen in the future the character 會 (wui5) is used before the verb, meaning “will/would”.

- In all of these examples, the time word [for example 聽日 (ting1 jat6) meaning today] is used at the start of the sentence, but note that you can also start with the pronoun and put the time word second.

Cantonese Particles

Particles play a very important role in Cantonese grammar.

They may seem strange at first, but they’re actually pretty easy once you get used to them.

A particle is a function word added to the end of a phrase or sentence.

In Cantonese, the particles at the end of the sentence change the inflexion and meaning of what you say.

咗 (zo2) and 緊 (gan2) – the particles we saw above – are two examples of particles used to express tenses in Cantonese.

But there are many much more than this.

One of the most common ones is the question particle – 呀 (aa3).

Simply add it to the end of the sentence and the statement becomes a question. For example:

- 你係James – (nei5 hai6 James)

- You are James

- 你係James呀? – (nei5 hai6 James aa3)

- Are you James?

Another example is 添 (tim1), which implies that something is happening again:

- 我唔記得帶我手機 – (ngo5 m4 gei3 dak1 daai3 ngo5 sau2 gei1)

- I forgot my phone!

- 我唔記得帶我手機添 – (ngo5 m4 gei3 dak1 daai3 ngo5 sau2 gei1 tim1)

- I forgot my phone again!

Some particles can also be used to add more subtle differences in the meaning, like 㗎啦 (gaa3 laa3), which implies that something is already a certain way, or something has already happened.

The example below using this particle was one of the first sentences my (Hong Kong) girlfriend taught me:

- 唔好意思, 我已經有女朋友㗎啦 – (m4 hou2 ji3 si3, ngo5 ji5 ging1 jau5 neoi5 pang4 jau5 gaa3 laa3)

- Sorry, I already have a girlfriend.

In this example, the particle at the end puts extra emphasis on the fact that situation is already this way, even though the sentence uses the word “already” – 已經 (ji5 ging1).

It is actually incredibly common with Cantonese for something to be stated in the sentence, and then reasserted with a particle after, and is one of the reasons why Cantonese is such an expressive language.

Particles are an important part of Cantonese and they will likely seem intimidating and confusing at first.

But don’t worry…

While there are a lot of particles in Cantonese, there are only a few particles that are necessary to understand basic grammar.

The most common particles will come up again and again, and you will master them before you know it.

Questions In Cantonese

We have already seen one way we can make questions in Cantonese: using the 呀 (aa3) particle.

But there is another common way to form yes/no questions. Let’s see it in action:

- 你鍾唔鍾意香港呀 – (nei5 zung1 m4 zung1 ji3 hoeng1 gong2 aa3)

- Do you like Hong Kong?

Here the verb 鍾意 (zung1 ji3), meaning “to like”, is stated once followed by a negative particle 唔 (m4), and then the verb again.

Putting 唔 (m4) in front of a verb makes that verb negative.

So essentially you are asking a yes/no question by saying “you like not like Hong Kong?”

The reply to this question would simply be “like” [鍾意 (zung1 ji3)], or “don’t like” [唔鍾意(m4 zung1 ji3)].

This same structure can be applied to any verb to make a yes/no question, giving you a simple way to form and reply to questions.

Easy, right?

Cantonese Measure Words

Another key feature of Cantonese grammar is the use of measure words.

Every time talk about a quantity of something, you have:

- a number

- followed by the measure word

- followed by the item

You have one measure word for each specific type or group of items.

For example, look at how 一張飛 (jat1 zeong1 fei1) – a ticket – is created.

- 張 (zoeng1), is the measure word used for pieces of paper

- 一 (jat1) is the number one

- 飛 (fei1) means ticket

Another example is 三部電腦 (saam1 bou6 din6 nou5), meaning “three computers”.

- 部 (bo6), is the measure word for electrical appliances

- 三 (saam1) is the number 3

Finally, look at 一個人 (jat1 go3 jan4), meaning a person.

The measure word in this example is 個 (go3).

This is by far the most common measure word in Cantonese, so it’s a good one to memorise right away!

It is so common if you forget any of the other measure words, you can just use 個 (go3), and the vast majority of the time it will perfectly acceptable.

And even if it’s not, people will still know exactly what you mean anyway!

The Two Twos In Cantonese

Something often causes a lot of confusion for Cantonese learners, is the fact that there are actually two ways to express the number two in Cantonese:

- 二 (ji6)

- 兩 (loeng5)

The first version, 二 (ji6), is used mostly in mathematical context – for counting, dates, or for constructing larger numbers.

兩 (loeng5) on the other hand, is typically used to say a pair of things or people.

This second one is probably more common in everyday conversation, so if you aren’t sure this would be the safest option to use.

Cantonese Grammar Is Relatively Straightforward

As you can see, at a basic level Cantonese grammar is actually really simple.

- Sentences in Cantonese follow a basic SVO (subject verb object) word order, similar to English.

- There are no words genders, and no verb conjugations in Cantonese!

- Each verb only has one form and you change the tense of a sentence by adding a single particle after the verb. This particle is exactly the same no matter what verb you use.

All in all, Cantonese grammar is much easier than the endless verb conjugations of Spanish or French or even the long list of irregular verb forms in English.

Learning To Read & Write Cantonese

If you want to be able to read or write, you’re going to have to learn Chinese characters.

The idea of learning thousands of Chinese characters may seem like a daunting task at first, especially when they look like a bunch of disconnected lines or squiggles.

But let me assure you, Chinese characters are incredibly logical and intuitive.

And a little bit of knowledge about how they work will go a long way.

Basic Cantonese Characters Are Based On Simple Pictures And Ideas

At a basic level Cantonese characters are based off simple pictures and diagrams.

Let me give you a few examples:

- 一 (jat1) – one

- 二 (ji6) – two

- 三 (saam1) – three

Do you notice how the number one is represented by a single line, two is represented by two lines and three by three lines?

Simple!

There are a few characters like this where the character resembles the basic idea it represents, making them incredibly easy to remember:

- 木 (muk6) – tree

- 人 (jan4) – person

These characters are simple pictographic representations of a tree and a person respectively.

All of the most basic elements/characters in Chinese originally came from this sort of origin.

With some of the characters, like 人, it is not immediately obvious that the character is a picture of a person.

This is because the characters have evolved, been changed and made easier to draw over the years to bring consistency to Chinese handwriting.

This, in turn, makes it easier for you to read and write Chinese.

Constructing Chinese Characters – Ideographs

Smaller characters, such as 人, are the building blocks of all Chinese characters.

Let’s call these building blocks primitive elements.

While it’s true that there are thousands of Characters in existence, every single character in Chinese is made up of some combination of just over 200 primitive elements.

For example, one common type of Chinese character is created when two primitive elements are combined together to create a new, larger character.

This is called an ideograph.

Let’s look at an example.

Remember, the character 木 (muk6), meaning tree?

When combining two of these 木 characters together, you have two trees next to each other, and the resulting new character means… woods!

- 林 (lam4) – woods

Another example is 休 (jau1).

Here you have a picture of a man leaning against a tree, representing… rest!

As you can see, the character system is actually very intuitive!

In this second example, it is not immediately obvious that the part on the left of 休 (jau1) is the same as 人, which can be confusing at first.

This is because the shape of primitive characters can change slightly depending on the position the take within a new character.

However, the good thing here is that there is only so many forms a primitive element can take when combining with new characters, and once you get used to the small changes, they really are consistent.

For example, the primitive element for person, 人, will always be in one of two forms.

The majority of the time it is in its original form. For example in 次 (ci3/sequence).

However, when it’s on the left, it resembles a T with a slanted top. For example, in the character 休 (jau1/rest).

Remember, there are only a little over 200 primitive elements that make up the building blocks for all Chinese characters.

Learning these simple characters or primitive elements first will give you everything you need to be able to break down more complicated characters into their constituent elements.

This will make remembering how to read and write them a lot easier.

Once you have learned the primitive elements, everything else will be putting together the same parts in different ways to create more characters.

This is similar to how we put together letters to form words in English.

How Many Characters Do I Need To Know?

So by now, you might be asking… “How many characters do I actually need to learn?“

A quick google search will show you that there are a frightening number of Chinese characters – over 50,000!

However, the good news is that the vast majority are never actually used in modern written Chinese:

- The Chinese government puts basic literacy at 2,000 characters

- In high school, students typically learn about 4,500 characters

- A university educated native will know upwards of 8,000 or so characters

From a learner’s perspective, 1,500 characters will be enough to understand 90% of written Chinese and give you an idea of what you are reading.

About 3,000 characters, should be enough to be able to read 99% of modern Chinese and be able to comfortably navigate everyday life.

As you can see the amount you need to learn very much depends on what your goals and aspirations are.

The first 2-3 thousand characters will be useful regardless and be used a lot in everyday life.

But if you keep on learning beyond that point, you study characters will be useful if you want to read or talk about specific topics.

So while a university educated student would know about 8,000, in reality you need to know significantly less than that in order to function perfectly well in the vast majority of situations.

Another thing to point out, is that you don’t necessarily need to learn how to write characters at all.

Learning to read and recognize Chinese characters, takes a lot less time and is a lot easier than learning how to write them.

Because Cantonese is typed phonetically on smartphones and computers, we can text or message our friends in Cantonese without ever learning how to write a single character by hand.

What’s more, if you are only aiming for a conversational level using spoken Cantonese, you can simply use learning materials which include Jyutping (such as Cantonese Conversations), and completely bypass learning characters altogether!

It really just depends on what your goals are.

6 Common Pitfalls To Watch Out For As A Beginner Cantonese Learner

Cantonese is very different from English, and it can be hard to know how to deal with some of the major stumbling blocks when first starting out in the language.

But if you know what to expect it makes the journey a lot easier, and you’ll be able to avoid some of the common pitfalls that derail so many learners.

1. Neglecting The Tones

Tones are probably the first major stumbling block you will come across.

The fact that changing the pitch changes the meaning of the word is very abstract at first for native English speakers.

What a lot of people do is look at the tones of words in isolation and try to commit them to memory.

However, this is a very long and ineffective process.

The first thing you should do when starting out is to tune your ears to the sounds of Cantonese and get used to the different sounds of the tones.

The best way to go about this is to listen to Cantonese dialogues many times over while reading the Jyutping and paying special attention to the tone markers.

If you forget what sound a tone number corresponds to then use the chart featured in this article.

You could even print out a copy and carry it with you or stick it on the wall above where you usually practice.

Click here to go back to the chart.

Listen, listen and then listen some more!

This process will take a few weeks before you remember all of the different pitches and sounds of Cantonese.

That’s why it’s so important to put a big emphasis on listening right from day 1 of your learning.

That being said, the process of distinguishing the tones in fast-paced conversation is a lot more difficult.

However, this becomes easier the bigger your vocabulary is as you can generally figure out a word’s meaning from context.

2. Mixing Up Spoken Cantonese And Written Chinese

This is something you really have to be careful of.

It is fairly common when first starting out to look up words in a dictionary, either online or via an app.

But when doing this, you can easily end up choosing the written form instead of the spoken one.

In general, if you avoid word lists and learn from context and dialogues, this really shouldn’t be much of an issue at all.

Another solution for this challenges brings me to the next potential pitfall…

3. Waiting Too Long Before You Start To Speak

Because of the spoken-written divide, it can be hard to know which words are actually used in everyday Cantonese.

For that reason, I highly recommend finding a teacher on italki, or a good language exchange partner, right from the start.

That way you can speak and try out words, and if you use the written form by mistake, you have a native speaker who can correct you and give you the spoken equivalent.

Another reason to start speaking early on is that it helps you notice the differences between the sounds of the Cantonese tones.

Practising saying the tones yourself, will help you notice the differences between them more than when you are just listening.

Additionally, it will help you identify gaps to work on and make sure you learn words that are relevant to you.

It’s easy to be scared to speak, but making mistakes is a part of the process of learning Cantonese.

Besides, even if you do make a few mistakes, it will give you funny stories and help you remember certain words in the future.

For more about how embarrassing mistakes can actually help you learn, watch this video I recorded with Lucas (The Cantonese Guy) about the topic. It’s something that every Cantonese learner has to go through at some point.

4. Trying To Do Too Much At Once

There are a lot of new features to get used to in Cantonese and trying to do too much at the same time will leave you feeling overwhelmed, frustrated and could eventually lead to you giving up.

This is why I am a big advocate for holding off on learning characters at the start, so you can build up your listening comprehension and speaking ability first.

This way you don’t have to tackle everything at the same time, and you can break down what you need to do into steps, and focus on one thing at a time.

5. Not Learning Characters Once You Reach An Intermediate Level

This one is more applicable for those of you living outside of a Cantonese speaking area.

If you are living in Hong Kong or Macau, once you are at an intermediate level you can practice speaking every day and really push your spoken level to the advanced stages.

However, if you aren’t that lucky then you need to compensate for having less speaking opportunities by focusing on input.

Reading is an incredibly powerful way of acquiring new words, even in Cantonese, and I think that not learning Characters will only hinder you in the long run.

If you can read, then there are books and comic books in Cantonese, as well as old movies and YouTube channels with Cantonese subtitles.

All of these things, allow you to take up your time and look up words at your own pace, something you could never do without knowing how to read the characters.

6. Learning Simplified Characters

While for Mandarin learners, choosing between simplified and traditional characters is a difficult choice, for Cantonese learners it is really a no-brainer.

Almost all Cantonese media being published today is from Hong Kong, meaning that it all is published with traditional characters.

If you learn the traditional set, there is a plethora of reading material as well as lots of videos with subtitles to learn from.

I am yet to see a single resource using simplified Chinese.

What’s The Best Way To Learn Cantonese As A Beginner?

Now that you know what pitfalls to avoid, you’re ready to really get started on your path to Cantonese fluency.

As a beginner, it’s often difficult to know where to start or what you should focus on.

In my experience, there are few simple shortcuts that you can take to quick start your learning and start making progress with your Cantonese in a relatively short space of time.

1. Focus On Listening From Day 1

Because of the reasons highlighted above, it is best to hold off on learning characters at the start and focus on listening.

Find a good beginners resource, and work through a dialogue at a time, listening every day and paying special attention to the tones to build up your listening comprehension.

2. Get A Flashcard App

When you are going through your dialogues and building up your comprehension you are going to across a lot of useful words & phrases that you want to remember.

Finding a flashcard app you like – my favourite is Anki – and transferring the words you want to learn over to your flashcards, can be a good way to help build up your active vocabulary before you start speaking for real.

Make sure when creating your flashcards that you capture the whole sentence in context.

There is nothing worse than knowing a bunch of words and not knowing how to use them.

When making flashcards I suggest you put the English on side 1, and the Jyutping and audio on side 2.

That way, when you see the English phrases you can practice saying the words in Cantonese from memory.

When first starting out, it will be extremely difficult to recall words.

Don’t worry! Just keep at it.

To avoid your flashcard decks getting out of control, be selective about the words/phrases you choose to learn and focus on what’s most relevant to you.

3. Use Mnemonics To Help You Remember New Words & Characters

In languages that are close to English, like German or Spanish, a lot of words sound similar to their English counterparts and so, are not too difficult to remember.

However, for languages that are very different from English, such as Arabic or Cantonese this is not the case.

This means that when first starting out it will be very hard to recall words, and they may even just sound like a bunch of noises to you.

Because Cantonese is very different to English it can be a little bit tricky to learn new words quickly.

This is where you need to be smart about how you learn.

The use of flashcards and being selective about what to learn will be a big help but there will still be words you want to learn that just won’t stick.

This is when I suggest using mnemonics.

A mnemonic is an association or link you form in your brain between new information and things you already know in order to remember something.

The more personal and relevant this is to you, and the more you can picture this in your head, then the greater the chance you’ll be able to remember it and use it to recall the Cantonese word it’s linked to.

Let me give you an example…

At one stage, I wanted to remember the expression “to go for a walk” in Cantonese, (pronounced “saan3 bou6”), but you keep on forgetting it.

So, decided to create a mnemonic to make it stick.

I imagined going for a walk on a sandy (saan3) beach with my dog Beau (bou6).

We walked him there many times, so it’s something I can easily picture in my mind.

I associate the sand with the sound “saan3”, and my dog’s name – Beau – with the sound “bou6”.

Voilà! I haven’t forgotten that expression since!

4. Make The Most Of Your Dead Time

If you go to work or school then you are likely to have a decent amount of dead time you can make use of during your commute every day.

Why not use this time to practice your Cantonese?

There are a few ways you can do this.

For example, if you’re using a beginner Cantonese course, why not save all the audio files on your phone or iPod?

I used to do this with the Pimsleur Cantonese programme – listening to the first half of a lesson on the way to work, and the second half coming home, going through a lesson each day.

Whatever resource you’re using, if it has audio, you can take it with you anywhere and take advantage of dead time throughout the day.

5. Find A Speaking Partner Or Tutor

After you have been learning for a month or two, you’ll finally start to make sense of some of the sounds of Cantonese, and a few of the words will start to stick.

That’s when it’s time to start speaking.

Find a good speaking partner or teacher, and just try to talk.

Start with simple introductions and everyday topics.

Just focus on keeping the conversation going and don’t worry too much about making mistakes.

The best place to find a teacher or tutor to practise with is italki.

Alternatively, if you want to find a language exchange partner, try contacting other learners on italki or use the HelloTalk app.

If you are unsure whether a word is from spoken Cantonese or written Chinese, then just ask your teacher or speaking partner!

It is also important, that you get feedback from your partner with your tones.

Try to set the goal of speaking 2-3 times a week if you can.

Combining this with your listening practice is a surefire way to get your Cantonese off to a good start.

6. Set Motivating Goals

To stay motivated and on the right track, setting short and long-term goals is vital.

When deciding on your goals it is important to consider what you want to be able to do in the language.

- Do you want to learn Cantonese to an academic level?

- Be able to read novels?

- Write essays?

- Or do you just want to be able to have enjoyable conversations with your friends from Hong Kong?

This is important because it will dictate what you choose to do and where you will put your focus.

An example of your first long-term goal could be to build up your speaking ability to a conversational level.

Once you’ve decided on your long-term goal, then set a series of short-term goals to help you achieve it. For example, these could be:

- Buy a beginner book and finish it after 2 months

- Find a speaking partner or tutor to work with after 1 month

- Aim to have 2-3 speaking sessions a week

- Transfer new important words to a flashcards app, and review them every day

- Find a good intermediate resource, such as Cantonese Conversations, and go through a new dialogue every 3 days

Once you’ve achieved your long-term goal you can set a new one, such as to learn how to read and write Chinese.

Resources To Learn Cantonese Online

I think in order to keep things simple, it’s best to try and stick to one romanization system if you can.

For that reason, the list below focuses on a few of my favourite resources that use Jyutping romanization.

Cantonese Listening Materials

Cantonese Conversations – I’m a huge fan of this resource! In a nutshell, it features full speed conversations by native speakers on a wide range of topics, will full transcripts in Chinese characters, Jyutping romanization and English. There are also additional vocab lists after each dialogue. Cantonese Conversations isn’t easy, and it’s a huge leap up from beginner materials such as Teach Yourself to something more natural like this, but the content is interesting enough to keep you engaged. This is full speed, no holds barred Cantonese, with all the supplements you need to be able to break it down into manageable chunks!

Cantonese Conversations – I’m a huge fan of this resource! In a nutshell, it features full speed conversations by native speakers on a wide range of topics, will full transcripts in Chinese characters, Jyutping romanization and English. There are also additional vocab lists after each dialogue. Cantonese Conversations isn’t easy, and it’s a huge leap up from beginner materials such as Teach Yourself to something more natural like this, but the content is interesting enough to keep you engaged. This is full speed, no holds barred Cantonese, with all the supplements you need to be able to break it down into manageable chunks!

Glossika – Glossika is an incredible resource for serious Cantonese learners who want to learn to understand and speak their new language quickly. Glossika helps you get used to all the different sounds and grammatical structures of the language through extensive listening.

Glossika – Glossika is an incredible resource for serious Cantonese learners who want to learn to understand and speak their new language quickly. Glossika helps you get used to all the different sounds and grammatical structures of the language through extensive listening.

Learn Cantonese With Podcasts

CantoneseClass101 – This is a great place to start for beginners, podcasts, dialogues with full line by line audio, transcripts as well as posts about cultural insights and aspects of the language. This includes some somewhat confusing topics if you haven’t come across them before; such as, tones or the divide between Spoken Cantonese and Written Chinese. This is a great first resource to use and I highly recommend it! (All lessons use Jyutping romanization, which is my favourite)

CantoneseClass101 – This is a great place to start for beginners, podcasts, dialogues with full line by line audio, transcripts as well as posts about cultural insights and aspects of the language. This includes some somewhat confusing topics if you haven’t come across them before; such as, tones or the divide between Spoken Cantonese and Written Chinese. This is a great first resource to use and I highly recommend it! (All lessons use Jyutping romanization, which is my favourite)

Cantonese Textbooks

Cantonese For Everyone – Textbook full of dialogues and pronunciation with everything you need to get started learning Cantonese. It comes with Jyutping romanization.

Learn How To Speak Cantonese

italki – This is my favourite website for finding teachers and affordable tutors to help practise my Cantonese. I use italki all the time to get that all-important speaking practice that helps me stay fluent.

italki – This is my favourite website for finding teachers and affordable tutors to help practise my Cantonese. I use italki all the time to get that all-important speaking practice that helps me stay fluent.

Memorising And Practising Chinese Characters

Remembering The Traditional Hanzi by James Heisig – This book breaks down 1500 of the most common traditional characters in modern Chinese, in a logical digestible manner using mnemonics, in an interesting way that none of the schools will teach you. Not everyone will like this book, slogging through a list of 1500 characters with no pronunciation or context isn’t for everyone. But if you do go for this, you will be able to learn all the characters inside the book in a matter of months, in a way you can’t do with rote memorization alone. What’s more is you will gain the ability to break down any Chinese character you see after that, into it’s much simpler parts in order to remember it

HelloTalk – What better way to practice recognizing and using Chinese characters than practicing with natives. This is a great way to meet people, learn about the culture and practice all at the same time. If combined with the “clipboard reader” on the app pleco, means you can have meaningful conversations with native speakers from relatively early on!

Cantonese Grammar Books

Cantonese: A Comprehensive Grammar – The most comprehensive Cantonese grammar book to date. Explanations are complete with examples sentences in both Yale and Characters along with English translations. There is even a section dedicated to all of the different particles in Cantonese.

Best Cantonese Dictionaries

- From the web – Canto Dict

- For mobile – Pleco

- Cantonese popup dictionary for google chrome

- If you read a lot on your computer, you need to have this add-on enabled. Then when you hover your mouse above a character, it will tell you the pronunciation and the English meaning. It works for compound words too, not just single characters. Great for helping you dissect difficult texts on the computer.

Now You're Ready To Start Learning Cantonese!

Armed with the tips and advice from this article, a clear game plan, and the help of a good teacher or speaking partner, Cantonese is not as hard as people make out.

You definitely can learn Cantonese if you break down the process into simple steps.

Cantonese has such a rich history and culture that the rewards for learning are much greater than the initial difficulty.

And you’ll soon discover just happy Hong Kong locals are when you choose to learn Cantonese to speak with them.

If you keep a consistent and solid routine and follow the tips in this article, you will be surprised at how far you can progress in just a few short months.

So what are you waiting for? Let’s get started!

Luke Truman is the founder of the Full Time Fluency blog, where he writes regularly about his Cantonese learning experiences.

I hope you’ve found this post useful!

If you have a friend learning Cantonese, please take a moment to share this post with them, or on social media – it would mean a lot to me!

I know this is a long post and it's difficult to take everything in all at once. That's why I've created a special PDF version of this article which you can download and refer to any time you need it! Click here to download the PDF version for free. And if you download the PDF, I’ll send you even more tips to help you as you continue learning Cantonese.

Click here to download the PDF now.

Olly Richards

Creator of the StoryLearning® Method

Olly Richards is a renowned polyglot and language learning expert with over 15 years of experience teaching millions through his innovative StoryLearning® method. He is the creator of StoryLearning, one of the world's largest language learning blogs with 500,000+ monthly readers.

Olly has authored 30+ language learning books and courses, including the bestselling "Short Stories" series published by Teach Yourself.

When not developing new teaching methods, Richards practices what he preaches—he speaks 8 languages fluently and continues learning new ones through his own methodology.