Here's a truth about learning German: nearly everyone struggles with German adjective endings or German adjective declension as it's also known.

Every textbook seems to contain endless tables and charts depicting similar adjective endings, seemingly chosen at random. Sound familiar?

Time to stop tearing your hair out! In this post, I'm breaking down German adjective endings into simple terms that you can understand.

I've also compiled all the information you need to know into one concise table. Finally, I'll show you how to choose the correct adjective ending in four easy steps.

By the way, if you want to learn German fast and have fun while doing it, my top recommendation is German Uncovered which teaches you through StoryLearning®.

With German Uncovered you’ll use my unique StoryLearning® method to learn German adjective ending and other grammar naturally through stories. It’s as fun as it is effective.

If you’re ready to get started, click here for a 7-day FREE trial.

Why Adjective Endings Matter

Adjective endings are a strange concept for English native speakers like you and I. However, for Germans, these endings fulfill a very specific purpose.

To understand, I want to show you how the English and German language compare.

English Grammar

Adjective endings don't exist in English, so why do you need them in German?

In English, we use word order to indicate who and what is the subject, direct object, and indirect object.

For example:

- The old woman is giving the young child a large piece of cake.

- The young child is giving a large piece of cake to the old woman.

- *A large piece of cake is giving the old woman to the young child.

By changing the word order, you change the meaning of the sentence. In some cases, changing the word order can turn a sentence into nonsense, like in the 3rd example.

German Grammar

In German, you can change the order of words around without changing the meaning of a sentence.

Take a look at the same sentences in German:

- Die alte Frau gibt dem jungen Kind ein großes Stück Kuchen.

- Dem jungen Kind gibt ein großes Stück Kuchen die alte Frau.

- Ein großes Stück Kuchen gibt die alte Frau dem jungen Kind.

You might think that each sentence has a different meaning.

However, each sentence means the same thing: “The old woman is giving the young child a large piece of cake.”

In German, adjective endings tell us who or what is the subject, object, and direct object, not the word order.

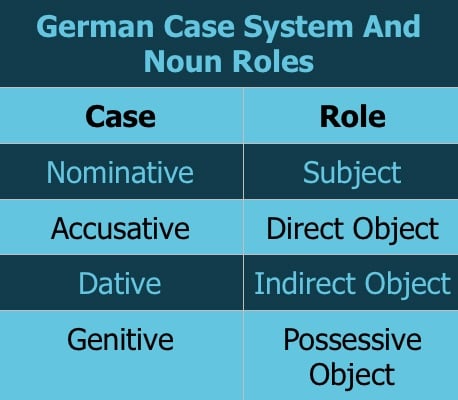

Remember The German Case System

You might remember that we can determine the role of a noun in a sentence according to the case.

You'll understand better when I break down the sentence from above.

- Die alte Frau (nominative subject – performs the action)

- Ein großes Stück Kuchen (accusative direct object – is affected by the action)

- Dem jungen Kind (dative indirect object – receives the action)

Notice how I've marked the definite articles, indefinite articles, and their corresponding adjective endings in bold.

Don't worry about how to choose the right ending yet. After my explanation, you'll have a much easier time understanding the consolidated table at the end.

How German Adjective Declension And Cases Interact

As you can see, the nouns themselves don't tell you which case they are.

Instead, the adjectives and preceding articles, or determiners, tell you which case you're using.

- Determiners – Words like “a”, “the”, “this”, “that”, “some”, “any”, etc.

- Adjectives – Words that describe nouns like “young”, “old”, “big”, “small”, etc.

In German, both determiners and adjectives take endings, also known as declensions or inflections, that indicate the noun's case.

Without these endings, you wouldn't know who was who or what was what.

I know what you're thinking: how will I ever make sense of the German language when the entire meaning of a sentence comes down to a single letter?

I admit, the system will take some getting used to in the beginning.

But, once you grasp the concept, you'll be surprised how much fun it is to change the word order around in German.

Strong, Weak, And Mixed Adjective Endings

In addition to figuring out the gender, number, and case of a noun, you'll also have to know whether the ending is strong, weak, or mixed.

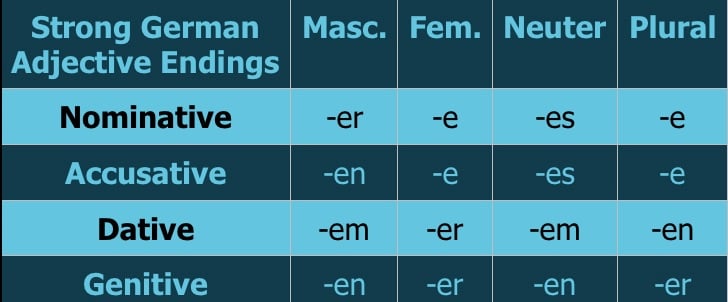

I know these facts might sound intimidating. But remember, there are only five possible endings altogether: -e, -er, -es, -en, and -em.

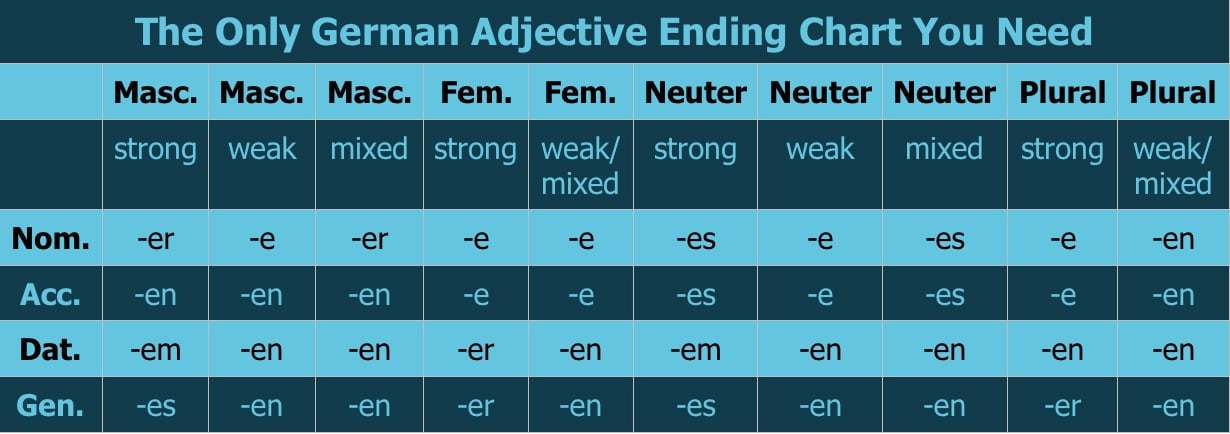

The tables below will help you understand how strong, weak, and mixed endings work. However, you don't need to memorize these.

You'll find a single simplified German adjective ending chart at the end of this post to use as a reference guide.

The 3 Categories Of Adjective Endings

Adjective declension refers to the process of selecting an adjective ending that agrees with the noun in gender and case. The first step is to identify if you're following a weak, strong, or mixed declension pattern.

- Weak – Use weak declension patterns following definite articles and pronouns such as der, die, das, dieser (this), derselbe (the same), derjenige (the one), jener (that), jeder (every), mancher (many), and welcher (which).

- You'll choose from 1 of 2 endings for weak adjectives, –e or –en.

- Mixed – Use mixed declensions after indefinite articles (ein, eine, einen, einem, and eines), possessive pronouns, and kein (none).

- For mixed declensions, you'll choose from 1 of 4 endings: –e, –en, –er, or –es.

- Strong – Use strong declensions when a noun has no article or after a pronoun such as ein wenig (a little), etwas (something), dergleichen (the same), or ein paar (a couple).

- You'll select 1 of 5 possible endings, –e, –en, –er,-em, or –es.

Weak declensions are the simplest because you only have to choose between two endings. Then, you'll be ready to learn about mixed declension patterns, with a total of four different endings. Finally, strong declensions use all five possible endings but will seem more manageable after learning the first two types.

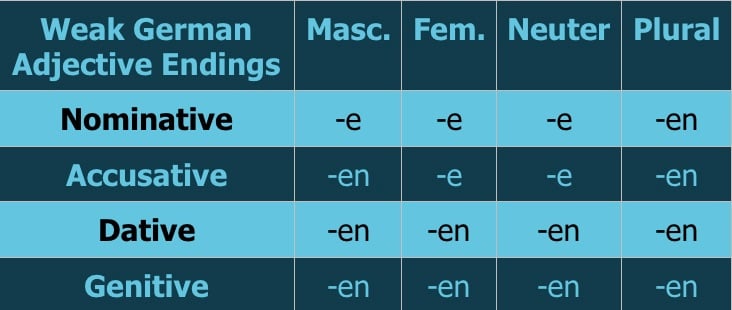

Weak Endings (Definite Article + Adjective)

Choose a weak ending after a definite article.

Notice that you only have to choose between an -e or -en ending. Plural, dative, and genitive always have -en endings.

The nominative and accusative cases always take an -e ending. The masculine accusative case takes an -en ending.

When you use the possessive (genitive) case, add an –s to long (two or more syllables) and –es to short (single-syllable) masculine and neuter nouns.

Let's take a look at some examples so you can see these weak German adjective endings in action:

- Example: das schöne Zimmer (the nice room)

Here, I have a definite article, das, and a neuter noun, so I need an -e ending.

Here are some more weak German adjective endings examples:

- Example: Der kalte Winter war lang. (The cold winter was long.)

- Example: Das große Theater wurde 1891 erbaut. (The big theater was built in 1891.)

- Example: Sie gab dem besten Student einen Preis. (She gave a prize to the best student.)

- Example: Wir haben das Fahrrad des schnellen Mannes gefunden. (We found the fast man's bicycle.)

I need to tell you about a few minor rule exceptions. But, don't worry, the exceptions make sense.

- Adjectives already ending in –e don't get another e.

- Example: “leise (quiet)” – Die leisen Tagen sind erfrischend. NOT leiseen. (The quiet days are refreshing.)

- Adjectives ending in –er and –el usually drop the –e before declension.

- Example: “teuer (expensive)” – Das teure Auto wird nicht ausverkauft sein. NOT teuere. (The expensive car won't sell out.)

- Hoch (high) is an irregular adjective that drops its -c during declension.

- Example: Wir haben die hohen Gebäude gesehen. NOT hochen. (We saw the tall buildings.)

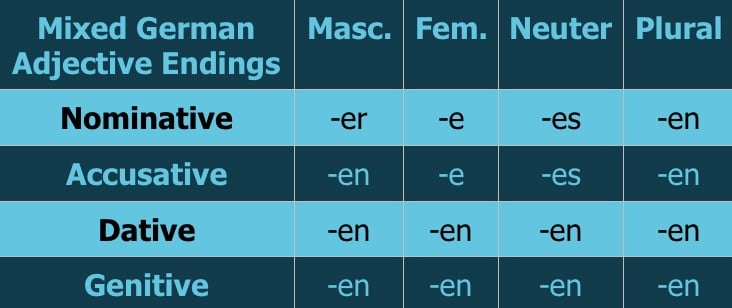

Mixed Endings (Indefinite Article + Adjective)

Use mixed endings after indefinite and possessive articles. A quick refresher – indefinite articles in English are “a” and “an”, while possessive articles are words like “my”.

Note that in the dative, possessive, and plural cases, your adjective always takes an –en ending. The feminine nominative and accusative cases both take an –e ending.

Similarly, both neuter nominative and accusative take an –es ending. The –er ending only appears in the masculine nominative case. Finally, the masculine accusative ending is also –en.

Here's an example to make things a bit clearer:

- Example: (m)ein schönes Zimmer. (my/a nice room)

Here, I'm dealing with an indefinite article, ein, and a neuter noun, so I'll take the -es ending.

Let's take a look at some more weak declension so this all starts to sink in a little more:

- Example: Ich habe einen grünen Mantel. (I have a green coat.)

- Example: Ein dicker Mann und sein kleiner Hund sind gerade an einem wunderschönen Park vorbeigegangen. (A fat man and his tiny dog just walked by a beautiful park.)

- Example: Eine junge Frau kaufte ihrer besten Freundin ein kleines Buch. (A young woman bought her best friend a small book.)

One trick to remember the mixed article declensions is to compare them to the simpler weak declension table. The declensions are the same for weak and mixed endings except for three. In three cases, you have ein without an ending of its own.

The masculine nominative, neuter nominative, and neuter accusative are the only three with endings different from the weak declensions.

Strong Endings (No Article + Adjective)

The final step to mastering German adjective declension involves strong endings preceding nouns without articles, the following quantifying indicators, and specific pronouns.

- dergleichen (the same)

- derlei (such)

- dessen/deren (whose)

- ein bisschen (a bit)

- einige (some)

- ein paar (a couple)

- ein wenig (a little)

- etliche mehrere (a few more)

- etwas (something)

- manch (some)

- viel (a lot)

- viele (many)

- wenig (little)

- wenige (few)

- wessen (whose)

- wie viel (how much)

See if you can spot differences and similarities from the previous two declension patterns in the table below.

If you're already familiar with the German cases, you'll recognize that strong endings follow almost the same declension patterns as der, die, and das.

Only the genitive case is different in the masculine and neuter cases. Instead of the expected -es ending, you use an -en ending.

- Example: schönes Zimmer (nice room)

Here, there is no article before the adjective, and I have a neuter noun, so I'll need an -es ending.

Let's take a look at some more strong adjective declension examples:

- Example: Heißer Kaffee wartet auf dich. (Hot coffee is waiting for you.)

- Example: Wessen alte Bücher sind das? (Whose old books are those?)

- Example: Der Geschmack von heißem Brot ist unschlagbar (or) Der Geschmack heißen Brotes ist unschlagbar.

Remember that you can either use von + the dative case or the possessive/genitive case, but the adjective endings are different.

Did you see all the similarities between the three tables?

The Only German Adjective Endings Chart You Need

Instead of memorizing several different charts, I've put together a single table that you can use as a reference to determine the correct adjective ending.

Note how the feminine and plural cases are the same for weak and mixed endings. The masculine and neuter endings are the same for weak and mixed endings in the dative and genitive cases.

Strong and mixed endings are the same for both masculine and neuter words in the nominative or accusative case.

Choose The Correct German Adjective Ending In 4 Steps

Next, I'll guide you step-by-step on how to choose the correct adjective ending when building a German sentence.

Step 1: Is the noun masculine, feminine, or neuter?

First, determine the gender of the noun. Let's use the first example sentence again – The old woman is giving the young child a large piece of cake.

In German, “the woman,” or die Frau, is a feminine noun.

Step 2: Is the noun singular or plural?

In the example sentence, there's one woman, so it's singular. Now, I've narrowed down my search for the correct ending to two columns.

Step 3: Are you using a definite (the), indefinite (a), or no article?

This information will help you decide whether to use a strong, weak, or mixed ending. My sentence has a definite article, so I need a weak ending. Now that I have the right column, I still have to choose the correct row.

Step 4: Do you need the nominative, accusative, dative, or genitive case?

Finally, you need to know what case you're using. You may have to identify the subject, direct object, indirect object, and possessive object first.

In my sentence, die Frau, is the subject, so I'll use the nominative case.

Now, I'm left with one column and one row that reveal that I need an -e ending. I can add this ending to any adjective between die and Frau.

- Example: die alte Frau (the old woman), die junge Frau (the young woman), die erste Frau (the first woman).

You can repeat this process for each noun in your sentence to figure out the right adjective ending.

When you have multiple adjectives, use the same ending for each one – more on that in a second.

Bonus: Comparatives, Superlatives & Consecutive Adjectives

Now that you've got the basics down – and yes, I know it all still seems a bit complicated but you'll get there – let's look at a couple of other situations where German adjective declension applies.

The good news is that they're pretty straightforward.

Adjective Declension In The Comparative And Superlative

When you use comparative and superlative adjectives (words like “better” and “best” or “taller” and “tallest”), use the same declension patterns as you would for other adjectives.

- Example: Ich suche bessere Hobbys. (I'm looking for better hobbies.)

Here, you need the ending for plural nouns in the accusative case using the strong declension pattern without an article.

- Example: Die erfahrensten Kandidaten haben die besten Chancen. (The most experienced candidates have the best chances.)

In this example, you have a nominative, plural adjective ending that follows a weak declension pattern for definite articles. You also have an accusative plural ending in a weak declension pattern.

- Example: Unsere nächsten Nachbarn sind weit entfernt. (Our closest neighbours are far away.)

Here, you'll notice a mixed declension pattern and a superlative adjective. In this case, you don't need to add a double –en ending since it already has one.

Declensions Involving Consecutive Adjectives

As I briefly mentioned above, when you have two or more adjectives together in a sentence, use the same ending for each consecutive adjective. Straightforward right?

Let's look at a couple of examples so it's crystal clear. And so that you can get some more German adjective endings practice.

- Example: Ich habe große blaue Tassen. (I have big blue cups.)

This example doesn't have articles, so you need to use strong declension rules.

- Example: Ich habe die großen blauen Tassen.(I have the big blue cups.)

Definite articles call for weak declension patterns for the adjectives in this sentence.

- Example: Ein seltener duftender bunter Kirschbaum blüht. (A rare fragrant colourful cherry tree is blooming.)

The indefinite article requires mixed declension patterns for its multiple adjectives.

German Adjective Endings: Patience And Perseverance Required

Learning German adjective endings requires repetition and practice. So don't give up on your German learning dreams just because of some pesky grammar!

(The Grammar Villain is a dastardly foe, but you can overcome him).

When in doubt, you can always just add an -e. German speakers will still understand you. And eventually, you'll develop a feeling for the right ending.

Adjective declensions are one of the more complicated concepts that you'll learn in German. So don't be discouraged if you can't always identify the gender or case of a noun.

Just keep on immersing yourself daily in German through stories, podcasts, movies or TV shows. It's this daily, regular contact with the language that will help you get familiar with the adjective endings over time.

And that's how you'll start using them the right way when you speak German.

Olly Richards

Creator of the StoryLearning® Method

Olly Richards is a renowned polyglot and language learning expert with over 15 years of experience teaching millions through his innovative StoryLearning® method. He is the creator of StoryLearning, one of the world's largest language learning blogs with 500,000+ monthly readers.

Olly has authored 30+ language learning books and courses, including the bestselling "Short Stories" series published by Teach Yourself.

When not developing new teaching methods, Richards practices what he preaches—he speaks 8 languages fluently and continues learning new ones through his own methodology.