If you're learning Chinese then I'm sure you've heard of Chinese New Year. It's the most eagerly awaited date in the Chinese calendar. And it's also the most famous and recognisable Chinese festival around the world.

However, beyond vague impressions of firecrackers, lion dances and lots of red decorations, many non-Chinese have little idea about the history or traditions of this key element of Chinese culture and identity.

So for anyone who wants to learn more, here’s my brief introduction to Chinese New Year, what it means and what the Chinese do to mark it.

Pro Tip

By the way, if you want to learn Chinese fast and have fun, my top recommendation is Chinese Uncovered which teaches you through StoryLearning®.

With Chinese Uncovered you’ll use my unique StoryLearning® method to learn Chinese through story…not rules. It’s as fun as it is effective. If you’re ready to get started, click here for a 7-day FREE trial.

Table of Contents

Chinese New Year: An Overview

Every year, sometime in January or February, the greatest movement of people on the planet begins as migrant workers throughout China begin the journey back to their hometowns to celebrate Chinese New Year with their families.

Usually known as 春节 chūnjié (Spring Festival) in China – and either “Chinese New Year” or “Lunar New Year” in other parts of the world – the festival is a time for family reunions, feasting and paying respects while seeing out the old year and welcoming in the new.

It is, without doubt, among the most important festivals in the Chinese calendar. And the celebrations involve various ancient traditions that date back millennia combined with more modern customs that have been incorporated more recently.

In many ways, Chinese New Year can be seen as being similar to Christmas in Western countries – or Thanksgiving in the US – when people have time off work and travel back to spend time with their loved ones.

Like Christmas or Thanksgiving, Chinese New Year is celebrated differently in different regions. And the traditions kept also vary from family to family.

Many of the older practices are derived from Confucianism, Buddhism or Taoism.

However, today it is also seen simply as a joyous occasion when people can spend time with those closest to them as they look forward with hope and optimism to a successful and prosperous new year.

Now let’s look at some of the various aspects of the celebrations in more detail.

When Is Chinese New Year?

The Chinese New Year dates are determined by the Chinese lunisolar calendar, which divides the year into 24 solar terms, making up 12 lunar months.

According to the Chinese calendar, the winter solstice falls in the 11th lunar month – and in practice, Chinese New Year usually falls on the second new moon after the winter solstice.

This means Chinese New Year’s Day is almost always celebrated on the day of the new moon closest to the start of the first lunisolar period of the year, the period known as 立春 lìchūn (Start of Spring).

This also corresponds to the first full moon after the final lunisolar period of the year, known as 大寒 dàhān (Big Cold).

Due to the way the lunar calendar is calculated, other dates are possible. But if all this seems a little complicated, a quick Google will tell you the correct date for any particular year – which is a much easier way to work it out!

In any case, on the Gregorian (Western) calendar, Chinese New Year always falls between 21st January and 20th February.

A Little History Of Chinese New Year

The start of the new lunisolar year has been celebrated in some form for several thousand years dating back at least to the Warring States period (475 – 221 BCE).

After this, the practice then spread throughout China thanks to the unification of the country under the Qin dynasty (221 – 206 BCE).

From the Han dynasty (202 BCE – 220 CE), celebrations involving ancestor worship, visiting family and wishing each other a happy new year were all recorded, customs that continue to this day.

The tradition of celebrations lasting until sunrise, known as 守岁 shŏusuì, dates back to the time of the Jin dynasty (266 – 420 CE), as does the first use of the term 除夕 chúxī to refer to Chinese New Year’s Eve.

By the Tang dynasty (618 – 907 CE), the practice of burning bamboo to make it explode had developed.

Later, after its invention in China sometime during the ninth century, gunpowder was placed inside the bamboo to create a bigger bang. And this is the precursor of today’s tradition of setting off firecrackers.

Indeed, one common Chinese word still used for “firecrackers” is 爆竹 bàozhú, which literally means “exploding bamboo”.

Since then, Chinese New Year traditions have continued to evolve. And celebrations today combine these ancient customs with several more modern ones.

One other important development to note came during the Cultural Revolution of the 1960s and 70s under Chairman Mao when Chinese New Year celebrations were banned in Mainland China.

They were once again permitted from 1980, but the legacy of this hiatus is that, in many ways, the celebrations held by overseas Chinese communities in places like Malaysia or Singapore are now more traditional than those in Mainland China.

15 Days Of Chinese New Year Celebrations

Although the most important dates of Chinese New Year are New Year’s Eve and New Year’s Day, the celebrations traditionally last 15 days, with each day having a special name and associated activities.

The first day of the new year is known as 春节 chūnjié, Spring Festival, and this is the day for setting off firecrackers, gathering with the extended family, exchanging red envelopes and other such customs.

After this, each of the following days has specific activities associated with it.

For example, the second day is known as 开年 kāinián (Year’s Beginning), and was traditionally the time for married daughters to visit their birth families.

On this day, beggars would also walk the streets with a picture of the god of wealth, 财神 cáishén, shouting 财神到 cáishéndào, meaning “the god of wealth has come”. They would then be rewarded with money for their efforts.

The 15th day is known as 元宵节 yuánxiāojié, the Lantern Festival, and it marks the end of the Chinese New Year period.

On this day, it's traditional to eat 汤圆 tāngyuán, glutinous rice balls containing fillings such as sweet red bean paste, black sesame paste, peanut paste – or, more recently, things like chocolate or custard.

Chinese New Year Traditions

Now let’s have a look at some of the various traditions that comprise Chinese New Year celebrations and where they come from.

Cleaning The House

Before the New Year arrives, one tradition is to clean the house to sweep away the bad luck from the previous year, preparing the way for good fortune in the year to come.

After cleaning, dustpans and brooms must be put away so the newly arrived good luck will not be swept away too.

Ancestor Worship

Ancestor worship has always been a part of Chinese New Year, and even to this day, it is customary to pay respects to one’s ancestors on Chinese New Year’s Eve.

However, whether this tradition is kept – and how formally or ritualistically it is done – depends on each family and their beliefs.

Deities

Along with the worship of ancestors, Chinese New Year is also a time to clean altars and worship and propitiate the various gods of the home.

Of these, among the most important is the Kitchen God, 灶君 zāo jūn, who flies back to heaven just before the New Year to report on the family to the Jade Emperor, 玉皇 yù huáng, the principal Chinese god of the heavens.

As a result, the Kitchen God is given ‘bribes’, and his lips are smeared with honey to sweeten his words in an attempt to ensure his report is favourable.

Firecrackers are let off to hasten his arrival in heaven, and his statue is then burnt. Afterwards, a new one is put in its place on New Year’s Day.

Again, the extent to which people follow these traditions nowadays varies from family to family.

Superstitions

Many superstitions about what you can and can’t do around the time of Chinese New Year exist.

It’s considered bad luck to have your hair cut after New Year since the Chinese character for “hair” 发 fà is the same as 发 fā, which can mean “make a fortune” – so cutting your hair represents cutting your fortune.

According to one traditional practice, after letting off firecrackers on New Year’s Eve, the door to the house is sealed and must remain closed until it is ritually opened again the next day. This is thought to prevent evil spirits from entering the house.

Debts must be paid before the New Year, including debts of gratitude, which is one reason why gifts are exchanged at this time.

If anybody breaks plates or swears on Chinese New Year’s Day, certain expressions must be uttered to appease the gods.

As mentioned above, sweeping is not allowed because it might sweep away any newly-arrived good luck, and lighting fires is also forbidden, so all food needs to be cooked before midnight on New Year’s Eve.

Firecrackers & Fireworks

An integral part of the celebrations involves the setting off of firecrackers and fireworks, and this dates back to some of the very earliest traditions surrounding Chinese New Year.

According to an ancient legend, a type of mythical beast called a nian used to terrorise villages at the start of the new year, appearing at night to eat the villagers – especially the children.

However, one year, an old man told his village that he would stay up to fight off the nian, and to do this, he put up red papers everywhere and armed himself with firecrackers.

The next morning, the man was still there, and nobody had been eaten – the man had saved the village because he had discovered that nian were afraid of loud noises and the colour red.

As a result, to this day, Chinese people let off firecrackers and fireworks to drive away evil spirits.

In the past, at midnight on New Year’s Eve, Chinese cities were lit up by thousands of fireworks as people went into the streets to let off their own personal stash.

Things have changed though, and in recent years, places like Beijing and Shanghai have banned individuals from letting off fireworks, providing an official firework display instead.

However, while the official display may be technically far superior – while reducing pollution and the risk of fire – it will never match the spectacular sight of the skies above the capital being lit up by innumerable fireworks being spontaneously let off from every street.

Lion Dance

Lion dances are performed, accompanied by the loud banging of drums, which is also related to driving away the evil nian.

Nowadays, lion dances are arguably easier to see in overseas Chinese communities than on the mainland.

Reunion Dinner And Food

A major part of the celebrations for each family is the reunion dinner, a lavish feast for which people return to their hometowns from all over the country.

A range of traditional dishes is served at the reunion dinner, each with its own special meaning. Here are some examples:

Fish

One of the most important elements of the feast is a fish dish, and this is because the Chinese word for fish, 鱼 yú, is pronounced exactly the same as 余 yú, meaning “surplus”.

In Chinese, the blessing 年年有余 nián nián yǒu yú (every year may there be a surplus), sounds the same as 年年有鱼 nián nián yǒu yú (every year may there be fish) – so eating fish for the New Year’s feast is considered auspicious.

To represent the surplus, some of the fish is eaten but not all of it – and the remainder, the ‘surplus’, is saved for the next day.

Dumplings

In the north of China, another important culinary element is 饺子 jiăozi (Chinese dumplings). This is because the shape of jiaozi is thought to resemble a 元宝 yuánbăo, a traditional gold or silver ingot, so making and eating them represents prosperity.

Often, families will sit down together to 包饺子 bāo jiăozi (wrap dumplings) before eating them at around midnight sometime after the main meal.

Auspicious ingredients are often included in the fillings, and sometimes a coin is placed inside one dumpling. The person who later finds the coin is then guaranteed good luck for the rest of the year.

Niangao

In eastern China in Shanghai and the provinces of Zhejiang and Jiangsu, people eat 年糕 niángāo, a type of New Year cake. The pronunciation is the same as 年高 niángāo, literally “year high”, which means “prosperous year”.

Other Chinese New Year Foods

These are just three of the traditional foods served during the reunion dinner, but there are many more, depending on the region.

Foods are often chosen because their names sound auspicious. One other example is 苹果 píngguǒ (apples), which are eaten because the first syllable sounds like 平 píng (peace).

Similarly, mandarins are eaten in southern China because their name sounds like “luck” in some Teochew dialects.

Decorations

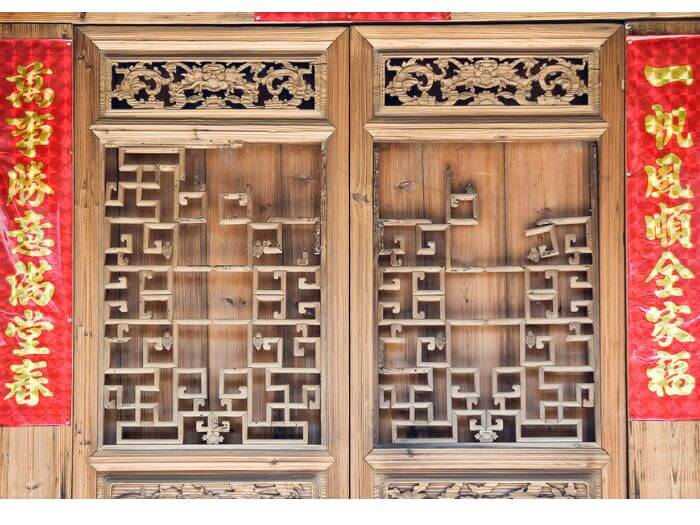

During Chinese New Year, people adorn their houses with traditional decorations.

Most people will be familiar with red lanterns, which are related to scaring away the mythical nian monsters that are afraid of the colour red. This is why red is also the predominant colour for all other traditional Chinese New Year decorations.

Another ubiquitous decoration is New Year couplets, known as 春联 chūnlián, which are hung on either side of a house’s door.

Couplets consist of two lines of poetry, and those chosen for New Year’s decorations usually express hope, happiness or optimism for the year to come.

The Chinese character 福 fú, meaning “good fortune”, “happiness” or “blessing”, is often placed in the middle of the door between the couplets or in other places around the house

However, the 福is usually hung upside-down, and this is because the Chinese word for “upside-down” is 倒 dào.

This word is pronounced the same as 到 dào, meaning “arrive”, so in Chinese, if you say 福倒 fúdào (fu upside-down), it sounds the same as福到 fúdào (good fortune arrives), which is seen as a way of inviting blessings upon the household.

Finally, cute representations of the Chinese zodiac animal for the year to come are also a popular decorative element seen in homes and shops everywhere.

Red Envelopes

An important New Year tradition is the giving of 红包 hóngbāo, or “red envelopes”, containing lucky money.

They are usually given by married members of a family to children and teenagers, and the custom is to give an amount of money ending in figures that are considered auspicious.

For example, 八 bā (8) is considered among the luckiest Chinese numbers since the pronunciation is close to the 发 in 发财 fācái, which means “get rich”. However, 四 sì (4) should be avoided due to its similarity to the word 死 sĭ, meaning “die”.

The practice of giving red envelopes comes from a legend that tells of an evil spirit called a 祟 suì that would pat the head of sleeping children on New Year’s Eve, after which the children would grow up to be learning disabled.

One New Year’s Eve, a couple tried to prevent their child from sleeping by giving him eight coins to play with. However, the child still fell asleep, so they placed the coins in a red envelope under his pillow.

Later that night, the sui appeared, but when it was about to pat the boy’s head, it saw the glint of the shining coins and was frightened away.

For this reason, money in red envelopes is sometimes called 压岁钱 yāsuìqián, which derives from 压祟钱 yāsuìqián, meaning “money to drive away the sui“.

Spring Festival Gala

A more modern tradition in Mainland China is the Spring Festival Gala, a TV variety show featuring music, dance, comedy and drama sketches – along with a good dose of fairly overt nationalistic propaganda.

It's broadcast on Chinese New Year’s Eve in China and around the world. Most families will gather around the television to watch it together – or at least have it on in the background – and as a result, it has become the world’s most watched broadcast.

You can find previous editions on YouTube if you want to check it out – and it’s also streamed live on YouTube each year.

New Year’s Songs

Just as Christmas in the West is associated with festive songs, Chinese New Year also has its own collection of classics that you’ll hear everywhere during the Chinese New Year period in China and other countries that celebrate the festival.

If you want to listen to some, go onto YouTube and search for ‘Spring Festival music’ to find countless compilations of all the best-known tunes.

Temple Fairs

Temple fairs, known as 庙会 miáohuì in Chinese, are held during the Chinese New Year period.

Originally, they were intended for worshipping the gods and asking for blessings – and this still happens – but nowadays, temple fairs, especially in northern China, are vibrant affairs with street food, fairground-style games, markets and more.

For example, if you are in Beijing at the right time of year, many of the city’s temples host lively fairs, and they shouldn’t be missed.

Inside, you can wander around the temple grounds sampling a range of tasty snacks such as 冰糖葫芦 bīngtánghúlù (fruit such as Chinese hawthorn dipped in maltose, which then hardens), barbecued pigeon or classic Beijing串儿 chuànr (barbecued skewers of meat).

Alternatively, if you’re feeling brave, you might have the opportunity to taste bugs, scorpions or tarantulas on sticks, all of which are sold for their dubious medicinal properties. Or perhaps just for the shock factor.

Chinese New Year FAQ

When exactly is Chinese New Year?

On the Gregorian (Western) calendar, Chinese New Year always falls between 21st January and 20th February.

How long is the Chinese New Year in 2025?

In 2025, Chinese New Year will begin on January 29 with the Year of the Snake. Celebrations generally last 15 days, ending with the Lantern Festival on the 15th day of the lunar month.

What is the animal of Chinese New Year?

Each Chinese New Year corresponds with one of the 12 animals of the Chinese zodiac. 2024 is the Year of the Dragon, while 2025 will be the Year of the Snake.

How long is Chinese New Year 2024?

Although the most important dates of Chinese New Year are New Year’s Eve and New Year’s Day, the celebrations traditionally last 15 days, with each day having a special name and associated activities.

Chinese New Year 2024 began on February 10 and lasted for 15 days, concluding with the Lantern Festival on February 24.

Useful Chinese New Year Phrases

Here are a few of the most important words and expressions related to Chinese New Year.

- 春节 chūnjié (Spring Festival), technically the first day of the Chinese New Year.

- 新年快乐 xīn nián kuài le (Happy New Year), a modern way to say this influenced by the English expression.

- 恭喜发财 gōngxĭ fācái (Have a prosperous new year), one of the most popular and well-known traditional New Year’s greetings. Literally, it means “congratulations, make a fortune” – the ‘congratulations’ part relates to congratulating people for surviving another difficult year.

- 年年有余 nián nián yǒu yú (May there be an abundance every year). This greeting is pronounced in exactly the same way as if you say “may there be fish every year”, which is why a fish dish is considered an essential part of the New Year’s feast.

- 财神到 cáishéndào (The god of wealth has arrived). You will often hear this in well-known Chinese New Year songs.

- 红包 hóngbāo (Red envelopes) containing money that are usually given to children and teenagers.

- 饺子 jiăozi (jiaozi – or Chinese dumplings) – that are traditionally eaten on New Year’s Eve in the north of China.

- 年糕 niángāo (New Year’s cake), traditionally eaten in Shanghai as well as Zhejiang and Jiangsu provinces.

- 爆竹 bàozhú (A common word for firecrackers).

- 鞭炮 biānpào (Strings of firecrackers that are set off together to make lots of noise and frighten off evil spirits).

- 守岁 shǒusuì (The practice of staying up till sunrise to welcome in the new year).

- 除夕 chúxī (Chinese New Year’s Eve).

- 庙会 miàohuì (Temple fair).

A Vibrant And Enjoyable Festival

Chinese New Year is one of the key dates in the Chinese calendar, and celebrating it is an important part of what it is to be Chinese.

It’s also an extremely vibrant and enjoyable festival. And if you ever have the chance to celebrate it in China or another country with a large Chinese population, it’s sure to be a memorable experience.

In the meantime, if you're looking for the best way to learn Chinese, why not apply the rules of StoryLearning and read books in Chinese?

Olly Richards

Creator of the StoryLearning® Method

Olly Richards is a renowned polyglot and language learning expert with over 15 years of experience teaching millions through his innovative StoryLearning® method. He is the creator of StoryLearning, one of the world's largest language learning blogs with 500,000+ monthly readers.

Olly has authored 30+ language learning books and courses, including the bestselling "Short Stories" series published by Teach Yourself.

When not developing new teaching methods, Richards practices what he preaches—he speaks 8 languages fluently and continues learning new ones through his own methodology.