When you learn Chinese you may not have the easiest time.

And one of the main reasons for this is the formidable character-based writing system it has that makes it difficult for beginners to read or write even the most basic texts.

However, there is a tool that can help you get started before you’ve mastered any characters at all, and it’s known as Chinese pinyin.

And in this post, I have all the info you need about what it is and how to start using it.

Pro Tip

By the way, if you want to learn Chinese fast and have fun, my top recommendation is Chinese Uncovered which teaches you through StoryLearning®.

With Chinese Uncovered you’ll use my unique StoryLearning® method to learn Chinese through story…not rules. It’s as fun as it is effective. If you’re ready to get started, click here for a 7-day FREE trial.

Table of Contents

Overview – What Is Chinese Pinyin?

Let’s start at the beginning – what is Chinese pinyin?

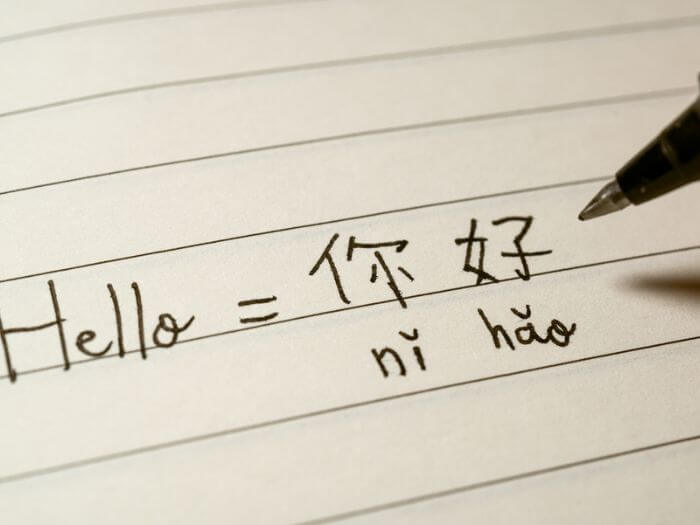

Pinyin – or 拼音 pīnyīn in Chinese, literally meaning “spell-sound” – is a system used to represent Chinese phonetically in Roman letters for people who don’t know characters.

It’s just one of many such systems, but it is now by far the most common, and it is a system with many advantages.

For learners of Chinese, it’s an essential tool that allows you to start reading and writing before you can do so using Chinese characters.

This allows you to use the StoryLearning method right from the beginning, something that would otherwise be impossible due to the number of characters you need to know to read even simple texts.

What's more, it’s a perfect guide to the pronunciation and tones of standard Chinese. Since it's totally regular with no exceptions, once you’ve learnt it, you'll always know exactly how to pronounce a word from how it is written in pinyin.

So in short, if you’re at the beginning of your Chinese learning journey, pinyin will quickly become your friend and ally as you strive to master enough characters to become effectively literate in Chinese.

But before we talk about learning and using pinyin, let’s look at its development and its place in the modern world.

A Little History Of Chinese Pinyin

Over the years, there have been many attempts to render Chinese in Roman letters. And before pinyin, one of the most important was the Wade-Giles romanisation system.

Wade-Giles was developed in the mid-nineteenth century by British diplomat and sinologist Sir Thomas Francis Wade.

It was then formalised by Herbert A. Giles, another British diplomat and sinologist, when he published his Chinese-English dictionary in 1892 – hence the name.

Another influential way of representing Chinese writing in letters was the “postal romanisation system”.

It was used for writing Chinese place names and was based on Wade-Giles – although many place names according to this system are quite different from their Wade-Giles equivalents.

It was this system that gave us many familiar but now dated names for Chinese cities. For example, most people will be familiar with Peking (Beijing) – while others include Tsingtao (Qingdao), Nanking (Nanjing) and Chungking (Chongqing).

However, in the 1950s, Chinese scholars began working on a new system that borrowed from earlier romanisation systems but also tried to improve on them.

The result became known as 汉语拼音 hànyŭ pīnyīn. It was officially adopted in China in 1958 and is the system still in use today.

Interestingly, Mao had originally intended to replace Chinese characters with pinyin entirely. But during a visit to the Soviet Union, Joseph Stalin convinced him to change his mind.

Where Is Chinese Pinyin Used?

Within mainland China, pinyin is the only official system of romanisation.

For visitors to China, it's most commonly seen on road signs where it is written below the characters to give the names of streets. It's also used wherever else characters need to be transliterated.

Since being adopted as the official system in China, its use has gradually spread around the rest of the world.

Nowadays, it's rare to encounter other forms of romanisation outside of dated history books. Or perhaps in Chinese restaurants that stick to older forms that might be more familiar to customers.

This is why you may still read about Mao Tse-Tung (instead of Mao Zedong), you may eat in a Szechwan restaurant (instead of one serving Sichuan cuisine) or you may find yourself ordering Peking duck (instead of Beijing duck).

However, all that has changed is the spelling – the Chinese pronunciation of these words has always been the same!

Chinese pinyin has now become the accepted system of romanisation in almost every country in the world. And it's also used by major international organisations such as the UN.

One exception is Taiwan where, due to political reasons, pinyin has never been fully adopted, instead taking its place among several competing systems in use there.

This is why the Taiwanese capital is still written as Taipei – while the pinyin spelling renders it as Taibei (台北 táibĕi).

What Is Chinese Pinyin Used For?

One reason pinyin was developed was to help Chinese children learn characters to boost literacy levels in China. And pinyin is now taught to young children as they begin writing their first characters.

Since pinyin is based on the pronunciation of standard Chinese, it's also used to teach speakers of other Chinese dialects the correct pronunciation of the national language.

At the same time, it's used to help speakers of other languages learn Chinese – for the same reasons.

It's the system you will use when you start learning Chinese to help you begin reading and writing. It will also help you learn correct Chinese pronunciation and tones, which is why pinyin is such a valuable tool for beginners.

Finally, pinyin is the most common input method for typing in Chinese. So if you learn Chinese, pinyin is something you’ll need to master right from the start.

How Pinyin Works: Initials & Finals

An important difference between how pinyin and English spelling work is that pinyin isn’t based on the same system of vowels and consonants as English.

Rather, pinyin uses what are known as “initials” and “finals” to make up the start and end of each syllable respectively.

The initial is always a consonant sound but isn’t always present – some syllables have no initial.

Finals, on the other hand, are vowel sounds, and all syllables must have a final. They can be simple vowels, compound vowels or vowels combined with a nasal consonant, either -n or -ng. Another consonant, -r, is sometimes also possible.

For an example of how it works, look at the following sounds:

- e

- he

- hen

- heng

- qian

The first is a syllable consisting of only the final, “e” – it has no initial. “E” is an example of a simple vowel sound. It is pronounced roughly like the “u” in “fur”.

The second has the same final, “e”, but this time it is combined with the initial “h” to make “he”.

The third has the initial “h”, but here, it is combined with the final “en” to make “hen”. “En” is an example of a final consisting of a vowel plus a nasal consonant. It is pronounced quite like the “en” in “taken”.

The fourth also has the initial “h”, but here, the final is “eng”, giving us “heng”. “Eng” is another final consisting of a vowel and a nasal consonant. It is pronounced like the “en” above combined with the “ng” sound from the English word ending “-ing”.

Lastly, this syllable has the initial “q” followed by the final “ian” (pronounced like “yen” as in the Japanese currency). This is an example of a compound vowel final.

This system of initials and finals is used to spell out the 400 or so possible syllables of standard Chinese.

For the beginner, you don’t have to learn all the possible combinations because most of them will come naturally through listening and repeating.

However, it’s useful just to be aware of this system since it will help you break down some of the more difficult sounds and pronounce them correctly.

Difficult Initials

I don’t have space here to give you a comprehensive guide to pinyin pronunciation. And you’ll find that in any good beginners’ textbook anyway.

However, I can mention a couple of tricky initials that are pronounced differently to in English.

S, X, Sh

The “s” sound in pinyin is pronounced about the same as in English and so is the “sh” sound. However, one that causes trouble is the “x” sound since English has no equivalent.

Unfortunately for many newsreaders, this sound is found in the name of the current Chinese president, Xi Jinping, and many fail to pronounce it correctly. He often gets referred to as either “Mr Shee” or “Mr See”, and neither of these is quite right.

Perhaps the best way to think of this sound is that it’s halfway between English “s” and English “sh”. To pronounce it, try to make a “sh” sound – but with the corners of your mouth pulled back as far as possible in an exaggerated smile.

C, Z

The “c” in pinyin is nothing like an English “c” – it’s pronounced like the “ts” in “cats”. This means the Chinese word 餐 cān (food, meal) is pronounced “tsan” and not like the English word “can”.

The “z” is more similar to an English “z” but is not identical. It’s pronounced like the “ds” in “pads” with the mouth in the same position as for “c” above.

For example, 在 zài (a word with many meanings, including “at” or “be at” among others), is pronounced “dzai”.

Q, Ch

Most people know that “Qing” (as in “Qing dynasty”) is pronounced like what we might write in English as “ching”.

However, the sound is not quite like English “ch”. Try pronouncing “ch” with your lips pulled back in a smile – a more accurate way to write it could be “tch”.

This is in contrast with the pinyin “ch”, which is much closer to the English “ch” sound.

R

The pinyin “r” is unlike anything in English and is extremely difficult to explain without audio, so I suggest you refer to your recordings or Chinese teacher for help with this one.

However, what I can say is that it is nothing like an English “r”.

Interestingly, when French president Emmanuel Macron tried to learn a sentence in Chinese for a speech he gave, he thought the word 让 ràng (to make, allow) sounded like the French name Jean – which at least gives you an idea of how different from an English “r” it is!

Chinese Pinyin Idiocyncracies

Other than the initials mentioned above, most of the others are quite similar to the equivalent letters in English.

And as far as the finals go, you’ll be able to master them simply by listening to Chinese pronunciation and repeating them. Also, see below for some tips on how to do it.

However, there are also a couple of idiosyncrasies that pinyin has that you need to be aware of, so let’s introduce them now.

U, Ü

The letter “u” represents two different sounds in Chinese, neither of which are found in English. However, for anyone who knows French, they are roughly similar to the “ou” in vous and the “u” in tu.

For example, 去 qù (to go) is pronounced with the French tu sound while 出 chū (to go/come out) is pronounced with the French vous sound.

Neither of these are pronounced like the English word “chew”, although this is the closest sound to either that we have in English.

Usually, depending on the initial, there is only one possibility – for example, following “q” or “ch”, the above pronunciations of “u” are the only ones possible.

However, with the initials “n” and “l” both pronunciations are possible, and in these cases, pinyin uses “u” for the vous sound and “ü” for the tu sound.This means, for example, 路 (road) is written in pinyin as lù while 绿 (green) is written as lǜ.

Note that to type “ü” when using a pinyin input method, you should use the “v” key – so to type 绿茶 lǜchá (green tea) you should type “lvcha”.

W, Y

A silent “w” is written at the start of a syllable beginning with “u” if there is no initial consonant. This means 五 wŭ (five) is pronounced “oo” and not “woo”.

A silent “y” is written at the start of a syllable beginning with “i” if there is no initial consonant. This means 一 yī is pronounced “ee” and not “yee”.

As a result, the correct pronunciation of pīnyīn is “pin-in” and not “pin-yin” since the “y” is silent.

Otherwise, these letters are similar to English – for example, the “w” and “y” are pronounced in words like 我 wŏ (I, me) and 鸭 yā (duck).

Chinese Pinyin And Tones

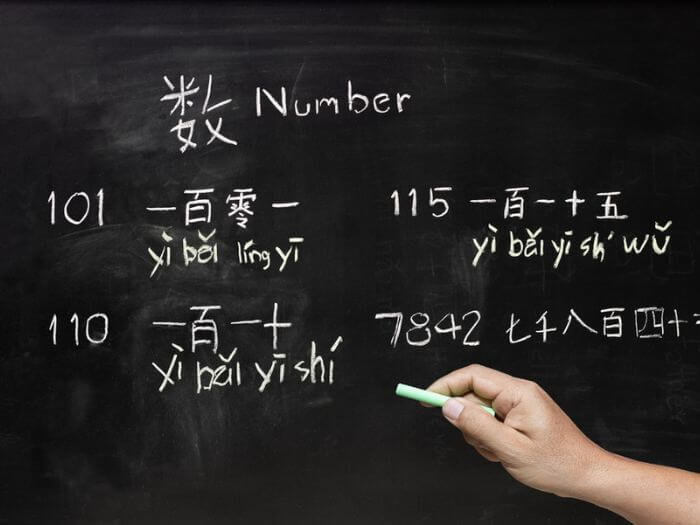

A big advantage of pinyin for learners is the way it represents the four tones of Chinese.

Four tone marks are used. They are written above the vowel carrying the tone to indicate whether a tone is high, rising, falling and rising or falling, as follows: ā, á, ă, à.

This system was designed to help speakers of non-standard Chinese dialects master the tones of standard Chinese. And they're also extremely useful for anybody else learning the language.

In general, tones are usually only written in learning contexts. So you'll find them in Chinese children’s schoolbooks as well as in textbooks for speakers of other languages who are learning Chinese.

However, pinyin is usually written without the tone marks in contexts such as road signs as well as in newspapers and books that include Chinese names or other words.

This is why “pinyin” as a loanword in English is usually written without tones – the tones are normally only included when the word is part of a Chinese text written in pinyin.

How To Learn Chinese Pinyin

One of the great things about pinyin is that it’s easy and intuitive to learn. Although it wasn’t created with English speakers in mind, most of the sounds represented by the letters are similar to English.

As we’ve seen, some letters in pinyin represent sounds that are quite different from their English counterparts. So if an English speaker who doesn’t know pinyin tries to read a pinyin word, there’s a good chance they’ll get it quite wrong.

However, you’ll soon pick it up through practice, so you don’t need to memorise all the details about initials and finals or other rules right from the beginning.

Instead, the best way is just to start using pinyin and absorb it naturally – and then to refer back to these rules and explanations later if you need to clarify anything.

Pinyin Pitfalls To Avoid

Finally, here are a couple of traps to avoid that will help you master pinyin and improve your Chinese pronunciation.

Don’t Read Words As You Would In English

The first thing to remember – and something that should be obvious but that often catches people out – is that you shouldn’t read a word as it would be pronounced in English.

A classic example of this is the word 很 hĕn meaning “very”.

As mentioned above, the final “en” here should be pronounced like the “en” in “taken” – so hĕn most definitely shouldn’t be pronounced like the English word for a female chicken. And yet it’s surprising how often you hear this rather embarrassing mistake!

Instead, you should get Chinese listening practice and repeat what you hear rather than how you think it should be pronounced according to the writing.

Don’t Let Your Accent Affect The Pronunciation

A common mistake is to allow your accent in English (or other language) to affect your pronunciation, which is natural but should be avoided.

For example, the tán in 天坛 tiāntán (the Temple of Heaven in Beijing) is pronounced with a short, open “a” that’s very different from the long “a” many speakers of American English would use to pronounce the English word “tan”.

In this case, the correct pronunciation is much closer to the standard British pronunciation of “tan”, but even then, it’s not quite the same. So listen to your recordings and copy what you hear.

Don’t Allow The Written Form To Confuse You

Finally, try not to become confused by the difference between the way something is written in pinyin and the way it’s actually pronounced. For example, the “iu” final in words like 六 liù and 九 jiù, “six” and “nine” respectively.

This sound is not especially difficult for English speakers to pronounce, but it can be hard to get your brain to accept the pronunciation due to the spelling.

When you see liu, your brain might want to pronounce it as something like “lee-oo” when it’s much closer to the English word “low” with a “y” slipped in the middle, giving you something like “lyow”.

If this confuses you, simply stop looking at the writing and listen to a recording or your teacher and then repeat the sound. With time, your brain will eventually accept that this is the correct spelling for this sound, and you'll be able to reproduce it correctly.

Can You Only Learn Chinese Pinyin?

If you can read and write Roman letters, you can start using pinyin immediately. And understanding the differences between pinyin and English (or other languages) takes little effort.

This is in contrast with Chinese characters, which take years to learn – and for which there are no shortcuts.

This may mean you might be wondering if you need to learn Chinese characters at all or if you can get by just with pinyin. And the answer depends on how far you want to take your Chinese.

If you're only interested in learning a few basic Chinese phrases, perhaps for an upcoming trip to China, you can stick to pinyin.

It will help you learn the correct pronunciation. And you'll have a standardised way to note down any new Chinese words you learn.

However, if you want to move beyond beginner level, there’s no substitute for characters.

Although Chinese children learn pinyin at school, most Chinese would find it difficult to understand a text in pinyin.

Due to the number of Chinese homonyms, it’s actually much easier to understand text in characters than in pinyin. And it’s also a slow job to type pinyin with tone marks.

For anyone serious about learning Chinese, learning characters is essential, and pinyin should be thought of as being like stabilisers on a bike (or “training wheels” for my American readers!).

The stabilisers help you get started, but you would never consider leaving them on forever. Most children get rid of their stabilisers as soon as they can, and you should see pinyin in the same way.

Chinese Pinyin FAQ

What is the Pinyin for Chinese?

Pinyin is the official Romanisation system for Mandarin Chinese, which uses the Latin alphabet to represent Chinese sounds. It helps learners with pronunciation and is widely used for teaching, typing, and linguistic study

What is the Chinese Pinyin for give?

The Pinyin for “give” in Mandarin is gěi (给). The tone mark above the “e” indicates that it has a third (low-rising) tone.

How many Chinese Pinyin?

There are about 400 unique syllables in Pinyin, which expand to around 1,600 different syllables when tones (four tones plus a neutral tone) are included. These cover the sounds of Mandarin Chinese.

Why did China switch to Pinyin?

China switched to Pinyin in the 1950s to help standardise Mandarin pronunciation, improve literacy rates, and provide an easier way for people to learn the language.

Pinyin also aids in typing Chinese characters and has become essential for modern communication and education.

Chinese Pinyin: Easy To Learn And Infinitely Useful

Although some of the explanations in this post might seem a little abstract or complicated at first, pinyin is extremely easy to pick up. And you’ll be able to use it to read and write Chinese quickly with almost no effort.

However, once you’ve started learning Chinese, it’s also worth coming back and reviewing the rules and the correct pronunciation of the more difficult initials and finals, something that will help improve your Chinese pronunciation no end.

At the same time, don’t forget that in terms of reading and writing, learning characters should always be your goal since you can never say you are literate in Chinese if pinyin is all you know.

And being literate means you can follow the rules of StoryLearning and read in Chinese to get fluent while having fun.

Olly Richards

Creator of the StoryLearning® Method

Olly Richards is a renowned polyglot and language learning expert with over 15 years of experience teaching millions through his innovative StoryLearning® method. He is the creator of StoryLearning, one of the world's largest language learning blogs with 500,000+ monthly readers.

Olly has authored 30+ language learning books and courses, including the bestselling "Short Stories" series published by Teach Yourself.

When not developing new teaching methods, Richards practices what he preaches—he speaks 8 languages fluently and continues learning new ones through his own methodology.