When you start learning Chinese, it might be something you look forward to or something you dread, but there’s no way around it – if you want to learn the language, you’ll have to learn how to read in Mandarin.

Fortunately, reading Chinese is not as hard as you might imagine, although you’ll certainly have to put in the hours. And to help, in this post I talk about how Chinese writing works, when you need to start learning – and the techniques you need to succeed.

By the time you've finished this post, you'll feel more confident about the Chinese writing system and you'll be ready to read in Mandarin. So that means you'll be able to learn Chinese through the power of story, by immersing yourself in Chinese books. Let's get into it then.

Pro Tip

By the way, if you want to learn Chinese fast and have fun, my top recommendation is Chinese Uncovered which teaches you through StoryLearning®.

With Chinese Uncovered you’ll use my unique StoryLearning® method to learn Chinese through story… not rules. It’s as fun as it is effective.

If you’re ready to get started, click here for a 7-day FREE trial.

Table of Contents

How Does Chinese Writing Work?

Before we talk about learning to read in Mandarin, we need to think about how Chinese writing works – because it’s quite different from almost any other system in the world.

In Chinese, words are written in characters rather than letters. In English, we use the Latin alphabet to spell out sounds with letters, but with Chinese characters, you can’t “spell” words.

Instead, each character represents a single syllable. And it also has a distinct meaning.

Two characters can have the same sound, but they are written differently and have different meanings. For example, the characters 他 and 她 are both pronounced tā – but the first one means “he” while the second means “she”.

The Meaning Of Characters

In ancient Chinese, words were monosyllabic, so each character represented one word. However, in modern Chinese, words can be monosyllabic or disyllabic, and some words even have three syllables or more.

This means that many modern Chinese words are made up of combinations of characters. So sometimes a particular character ‘means’ something, but that character isn’t necessarily the word you use for that thing.

This might seem a little difficult to understand, so let’s take a look at some examples:

The character 口 kŏu means “mouth”, but you don’t use it to say “mouth” – the word for mouth is 嘴 zuĭ.

However, 口 is found in combinations like 进口 jìnkŏu (entrance – literally “in mouth”), 出口 chūkŏu (exit – literally “out mouth”) and 口语 kŏuyŭ (spoken/oral language – literally “mouth language”).

In contrast, the character 火 huŏ means “fire” and is also the word we use for “fire”. Similarly, 手 means “hand” and is also the word for “hand”.

So each character has an intrinsic ‘meaning’ – but it may or not be the word we use to talk about that thing.

Different Types Of Chinese Words

Chinese words are made up of individual characters or combinations, and there are different ways this can happen.

We’ve already seen that 火 huŏ and 手 shŏu can be used alone, but they are also found combined with other characters.

For example, the character 车 chē means “vehicle” or “car”, but in combination, 火车 huŏchē means “train” (literally, “fire vehicle”). In the same way, 机 jī means “machine” – and when combined to make 手机 shŏujī, the meaning is “mobile telephone” (literally “hand machine”).

Alternatively, many disyllabic words, usually for things, simply add the character 子 zi,with a neutral tone, at the end (子zĭ with a third tone means “child” but is not usually used alone).

Here are some examples:

- 筷子 kuàizi (chopsticks)

- 杯子 bēizi (cup)

- 桌子 zhuōzi (table)

- 脑子 năozi (brain)

- 孩子 háizi (child)

- 鼻子 bìzi (nose)

In words like these, 子 zi doesn’t have any meaning – it is there solely for reasons of sonority.

As an aside, if you take the 脑 năo from 脑子 năozi (brain) and combine it with 电 diàn, the character for “electricity”, you make 电脑 diànnăo, which literally means “electric brain”. This is the Chinese word for “computer”. And by now you should be starting to get an idea of how it works!

Different Character, Same Pronunciation

As we saw with 他 and 她 (both tā, “he” and “she” respectively), two characters can have the same pronunciation but different meanings. Another is example is 快 kuài (fast) and 筷 kuài (as above in 筷子 kuàizi, (chopsticks)).

It’s common to find several characters with the same pronunciation, but they are not interchangeable. Although the sound is the same, you must use the correct one or the sentence would be meaningless.

Even more common are characters with the same pronunciation but a different Chinese tone. For example, 只 is pronounced zhĭ while知 is pronounced zhī. The former means “only” while the latter is a character you are likely to first meet in the word 知道 zhīdào, (to know).

In fact, this system makes sense. Each character has its own individual meaning, pronunciation and tone. So Chinese text in characters is much easier to understand than text written in pinyin (especially without tone marks).

This is because there is never any doubt over the meaning or pronunciation of a character on the page – as long as you have learned that character, of course!

Same Character, Different Pronunciation

There is one complication, however, because some characters have more than one possible pronunciation, depending on their function in the sentence.

Usually, the difference is just the tone. We just saw that只 zhĭ means “only”. However, this character can also be used as the measure word for birds and some animals (among other things). And when used like this, it is pronounced zhī.

Look at these examples:

- 我只有一个 wŏ zhĭ yŏu yí gè (I only have one)

- 一只狗 yì zhī gŏu (One dog)

However, the meaning – and pronunciation – is always clear from the context.

This kind of thing is not uncommon. Less common are words that have two completely different pronunciations. For example, 行 is pronounced xíng and means “ok” or “alright”. However, when used in the word 银行 yínháng (bank), the pronunciation changes to háng.

Fortunately, there aren’t too many words like this, so they’re easy to remember.

How Does Chinese Look On The Page?

That’s a brief overview of how Chinese writing works, but how does it look on the page?

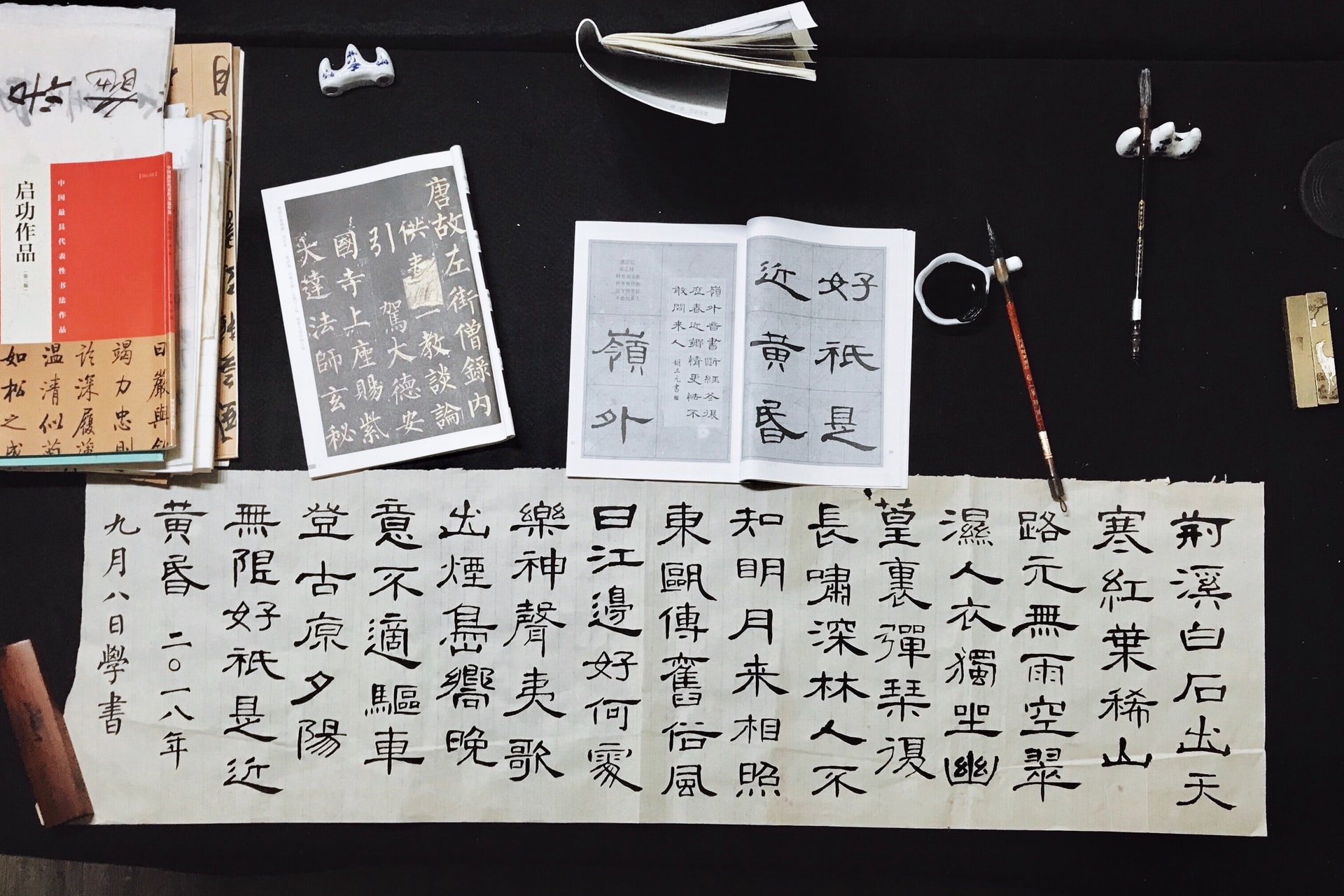

In the past, Chinese was traditionally written in columns from top to bottom, with the columns running right to left (so the first column you read is on the right and the last on the left).

Nowadays, in mainland China, Chinese is written horizontally from left to right, just like English, although the traditional format is still popular in Taiwan.

In the past, characters were written from right to left above gates, on temples or on other buildings. This practice is still found in overseas Chinese communities, but on the mainland, characters now go from left to right.

Still, it’s an interesting quirk that Chinese is just as easy to read written in any direction.

When we write in pinyin, we separate words with spaces, as in English. However, with characters, they all occupy the same amount of space on the line with no gaps to indicate individual words.

Again, with characters, this makes sense because sometimes it’s not clear what constitutes a separate word.

For example, in pinyin, it’s not obvious whether verb-object constructions like 吃饭 chī fàn ((to eat), but literally, “eat rice”) or 唱歌 chàng gē ((to sing), but literally, “sing song”) should be one word or two. But with characters, this question simply doesn’t arise.

In terms of Chinese punctuation, modern Chinese uses the same commas, question marks and exclamation marks as English, and a Chinese full-stop looks like this: 。Chinese also has a special punctuation mark used in lists that looks like a backwards comma:

- 老鼠、牛、老虎、兔子、龙、蛇

- Lăoshŭ、niú、lăohŭ、tùzi、lóng、shé

- Rat, ox, tiger, rabbit, dragon, snake

These, of course, are the first six animals of the Chinese zodiac.

When Should You Start Learning To Read In Mandarin?

If you’re serious about Chinese, the answer is to read in Mandarin as early as possible. As you’ve seen, for Chinese, using characters makes much more sense than using an alphabet. And if you want to go beyond learning just the basics, you won’t be able to rely on pinyin.

If you are taking classes, your textbooks will almost certainly contain characters alongside the pinyin. And after the first few weeks, your teacher will probably start teaching you reading and writing.

If you are studying alone, you can still learn to in Mandarin without a teacher as long as you have the right resources and techniques. So let’s have a look at that now.

Tips To Read In Mandarin

Now I have some good news and some bad news – so let’s start with the good.

Learning to read in Mandarin is not especially difficult, and with dedication and determination, anybody can do it.

But now the bad.

There is no secret magical shortcut, and it’s something that takes time and effort.

Chinese children spend far longer learning to read and write than children who speak European languages. And when you start learning Chinese, you will have to do the same.

The key is building a good learning habit and practising characters every day. With daily practice, you will progress rapidly, but if you only study once a week, it will be tough going.

And to finish, here are a few tips that will help you improve your reading as quickly as possible.

Learn Chinese Reading And Writing Together

The traditional way to learn Chinese characters is writing them out lots of times. And this is still the most effective technique.

By writing them, you become intimately familiar with them, learning the correct stroke order and fixing them in your long-term memory. This familiarity will, in turn, help with your reading too.

Identify Radicals And Phonetic Elements

Chinese characters are not just made up of random lines, and identifying the different parts can help

First, learn to identify what’s known as the radical to give you a clue to the meaning.

For example, the radical in 嘴 zuĭ (mouth) is 口 kŏu, the “mouth” radical, and this gives you a big hint about the meaning. Similarly, 吃 chī (eat) also contains the “mouth” radical, and this should help you remember too.

Characters also contain a ‘phonetic element’ that can tell you about the pronunciation. For example, 请 qĭng (invite) and 清 qīng (clear) share the phonetic element 青qīng (“green crops”, “green”, “blue” or “black”). As you can see, the pronunciation of the three characters is similar. And this is something else that can be helpful.

Check out my post about Chinese radicals and phonetic elements for more information.

Use Dialogues From Your Textbooks

Use your textbook to practise reading and writing dialogues. Cover up the characters and write them out from the pinyin. Then cover up the pinyin and read the text aloud from the characters.

The more you do this, the easier and more natural it will become, and your reading, writing and pronunciation will all improve.

Use Graded Readers

One thing that makes Chinese difficult to learn is that you can’t start reading until you know enough characters.

It’s not like French or Spanish where you can pick up a newspaper and guess the words you don’t know. With characters, you know them or you don’t – you can’t ‘work them out’ from the way they look.

This is why graded Mandarin readers are highly recommended – because you can practise reading texts with characters suitable for your level. Usually, they have a pinyin transcription and a vocab list too, so they’re ideal for improving your reading skills as well as your overall ability.

Use Reading Apps

Nowadays, lots of useful Chinese apps exist for reading in Mandarin, and many are free. Just like graded readers, they let you practise reading texts at your level – and often, they include interactive features like personal word banks and the possibility to listen to the text being read out.

- Skritter app

One of my top recommendations for learning Chinese characters is the Skritter app. It lets you practise reading and writing, using algorithms to train you on characters you struggle with most. You have to pay for a subscription, but if you are serious about Chinese characters, it will be money well spent.

- Language exchange apps

Language exchange apps like Tandem or HelloTalk are perfect for practising typing and reading characters. Once you start, you will see that many of basic characters occur frequently – and you can always look up any you don’t know in a dictionary.

Make Time To Read In Mandarin And Use Every Opportunity To Practise

More than with other languages, it’s vital to set aside time to work on reading in Chinese because if you don’t, the characters won’t learn themselves. Also, seize every opportunity to practise.

For example, if you go to a Chinese restaurant, take a photo of the menu and work out what all the characters for the names of the dishes are. In your spare time, doodle in Chinese and write out sentences to read back to yourself.

Above all, try to make reading and writing Chinese a part of your daily life – and you will soon see how those once mysterious and impenetrable symbols quickly begin to seem more familiar.

Read In Mandarin FAQ

How Mandarin is read?

Mandarin Chinese is read from left to right, horizontally, similar to English. Modern Chinese writing is typically presented this way, especially in printed materials, books, and digital text.

In traditional formats, like some classical texts and calligraphy, Chinese can also be written vertically from top to bottom, with columns starting from the right side of the page and moving left.

However, this style is less common in everyday use and is mainly seen in older or formal works.

Each character represents a word or concept, so understanding the meaning requires knowing the specific characters, which do not directly indicate pronunciation.

Instead, Pinyin, a romanisation system using Latin letters, helps learners understand pronunciation.

What is du shu in Chinese?

“读书” (dú shū) in Chinese means “to read a book” or “to study.”

读 (dú) means “to read” or “to study.”

书 (shū) means “book.”

In a broader sense, “读书” can imply studying or pursuing education, not just reading books. It’s often used to talk about academic study, such as “他在读书” (tā zài dú shū), meaning “he is studying.”

Read In Mandarin – Stick With It As It’s Easier Than You Might Think

The Chinese writing system is undeniably one of the major hurdles when tackling this challenging but fascinating language.

However, mastering the 3000 or so characters you need to read a newspaper or perhaps tackle a simple novel is far from impossible, and as long as you practise regularly and don’t give up, becoming literate in Chinese is an ambitious but achievable goal.

Ready to get started? Sign up for a FREE 7-day trial of my comprehensive online course, Chinese Uncovered, and start learning Chinese characters through story.

Olly Richards

Creator of the StoryLearning® Method

Olly Richards is a renowned polyglot and language learning expert with over 15 years of experience teaching millions through his innovative StoryLearning® method. He is the creator of StoryLearning, one of the world's largest language learning blogs with 500,000+ monthly readers.

Olly has authored 30+ language learning books and courses, including the bestselling "Short Stories" series published by Teach Yourself.

When not developing new teaching methods, Richards practices what he preaches—he speaks 8 languages fluently and continues learning new ones through his own methodology.